Björn Lundberg, Lund University and David Larsson Heidenblad, Lund University

After 18 months of digital campaigning, young people are again taking to the streets demanding climate justice, with attention now directed at the UN climate summit in Glasgow and a protest march on November 5.

When a 15-year-old Greta Thunberg began her Skolstrejk för klimatet (school strike for climate) outside the Swedish parliament in 2018, few would have guessed that her initiative would spur worldwide protests. Due to its rapid international impact, this movement has been described as a new form of political mobilisation, but such generalisations fail to consider the much longer history of young people’s global awareness and action. As historians who have researched environmental youth activism in Sweden “before Greta”, we argue that what you see today is rooted in a Scandinavian tradition of youth empowerment and global awareness.

We first want to note that children’s participation in social and political issues has been facilitated by specific notions of childhood in the Nordic countries. The idea of the autonomous and competent child has been described by researchers as a characteristic feature of the “Nordic model of childhood”, influencing child rearing and public policy for several decades. While the elements of this model are not unique to the region, the notion has had a lasting impact upon several generations of Swedish children, teaching them the value of independence and making their voices heard.

There has also been a long-standing ambition in Sweden to foster young people’s global consciousness. Today, climate change dominates the political agenda, but this is not the first global issue to engage young people. In the early post-war era, children and young people played a key role when development aid became a new area of Swedish foreign policy. Polls showed that young people were more susceptible to the message of international solidarity than older generations and thus became crucial target groups for efforts to raise popular support for aid policy.

Older people on trial

With the emergence of modern environmentalism and the “ecological turn” around 1970, when knowledge of a global environmental crisis became more widespread, children and young people were mobilised to take action.

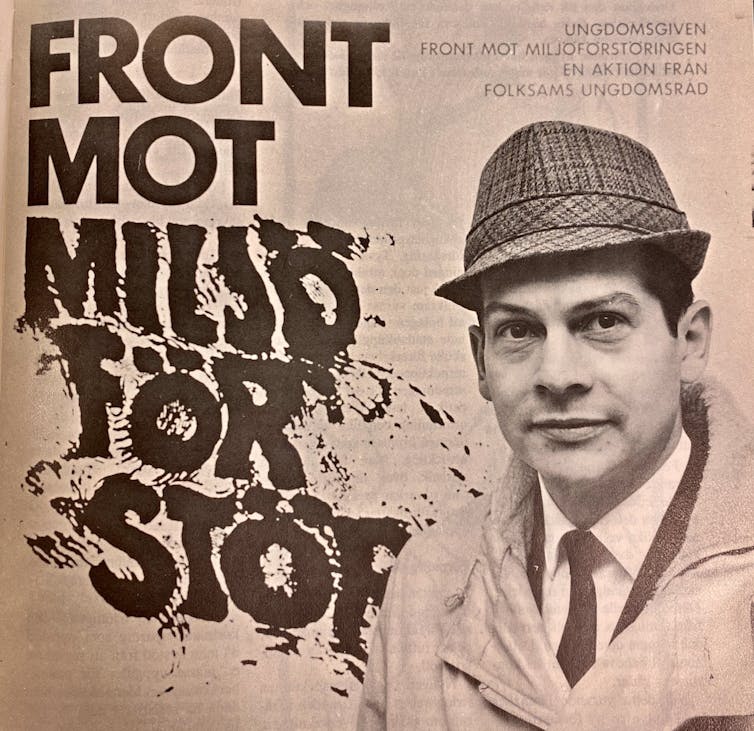

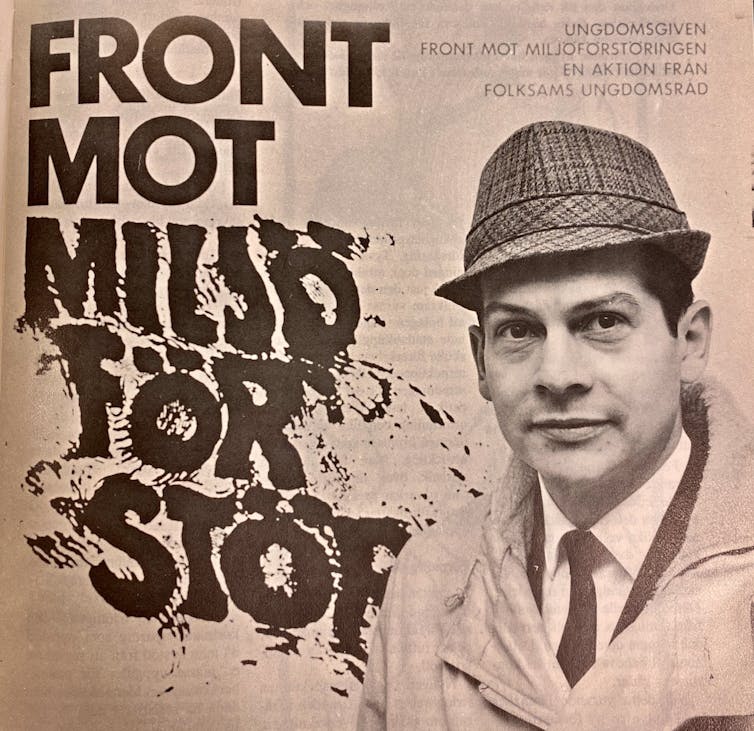

One of the first major Swedish initiatives was the campaign “Front against environmental degradation”, launched by insurance company Folksam in 1968. The corporation had strong ties to the social democratic government and launched a national competition where young people were given the task of documenting environmental problems in their local communities. These inventories formed the basis for a series of public hearings in 1969, where young people put an older generation of politicians, public officials and industry leaders against the wall. With an average attendance of 500 people, these hearings were considered a public success.

From a contemporary viewpoint, the young interrogators’ demands for clean air and sewage treatment appear modest, but during the campaign finale – an “environmental parliament” in January 1970 – the Swedish minister of agriculture considered it ungrateful of the younger generation to demand change too rapidly. With stubborn and tireless work, he argued, further environmental destruction would be prevented in due time.

Youth-led activism

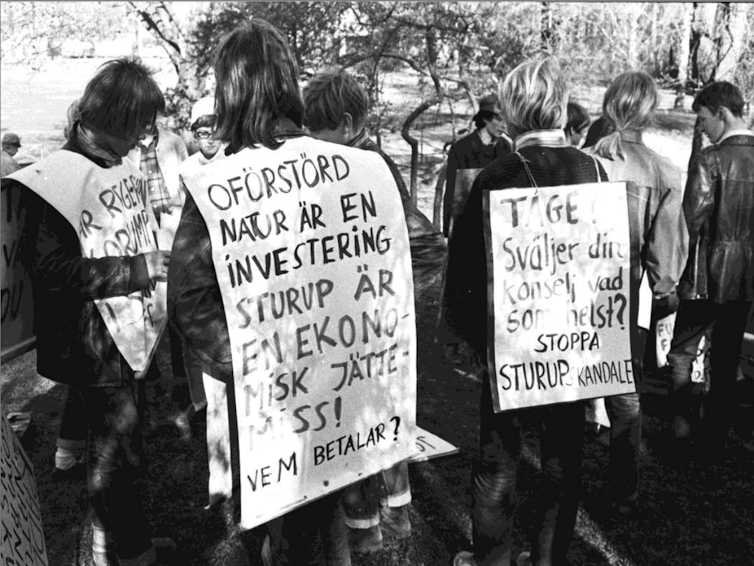

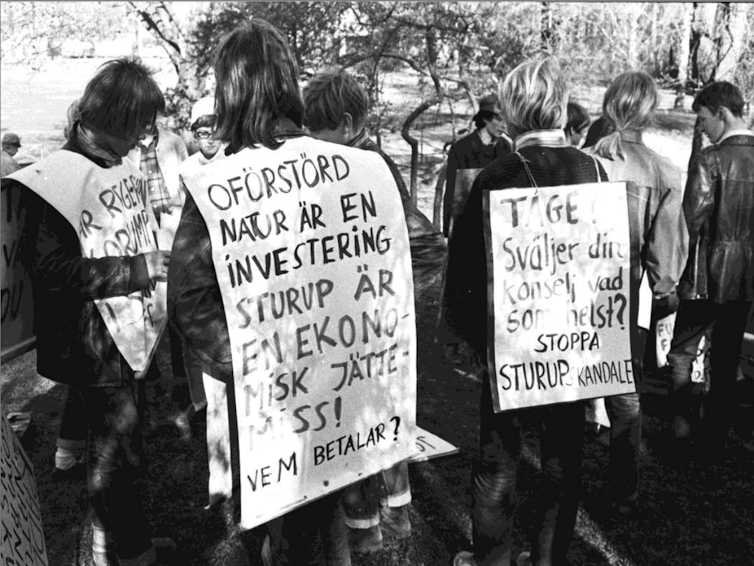

Modern Swedish history provides several examples of youth-led activism on global issues. While the Folksam initiative was adult-organised, other campaigns and initiatives have relied on self-organisation by the younger generation. An early example of this was Fältbiologerna (literally: “the field biologists”), the youth division of the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation, which became a hotbed for environmental activism.

In addition to hiking in the wilderness, the field biologists started to demonstrate and make spectacular direct actions. They marched under banners such as “killing nature is suicide” and “your children protest against your short-termism”. In the early 1970s, they mailed disposable bottles and cans to the authorities, to spur a transition to recycling.

Another striking example was the annual campaign Operation Dagsverke, “operation day’s work”, that emerged in the early 1960s. Led by rather loosely organised student unions, the campaign expanded rapidly and soon involved tens of thousands of schoolchildren, raising money for projects in the global south.

This campaign relied on two of the main resources that children have often mobilised in efforts to create change: time and spontaneous activity. By dedicating an entire day for fundraising, children took time off from school to invest in the future of humanity – a line of thought that has also been important in the school strike movement. The field biologists and operation day’s work both included a kind of age-integration, where older teenagers organised and coordinated the efforts of younger children, a feature that they share with contemporary activism.

A year after Greta Thunberg began protesting outside the Swedish parliament, climate protests took place globally and she was named “person of the year” by Time magazine. This impact was rendered possible by digital technology and social media platforms, but the emergence of this movement should also be understood against the backdrop of a more than 50-year-old political culture of environmental youth activism.

Björn Lundberg, Researcher, History, Lund University and David Larsson Heidenblad, Associate Professor, History, Lund University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.