On 17th January 2016, Rohith Vemula, a Dalit research scholar at the University of Hyderabad had to end his life after being unjustly suspended. Already brewing with anger and agony, the institutional murder of Rohith triggered the student community. The brilliant letter penned down by Rohith, which in his own words, the only letter an aspiring writer like him could write, affectively moved the student groups in general and marginalized communities in particular. It sparked a country-wide movement, forcibly bringing the anti-caste sentiments into the centre stage of student politics.

Post-Mandal Assertions

Indian academic space has been filled with upper-caste bodies, Hindu desires and Brahmanic ethos. However, this has been moved down to generations in the garb of secular and liberal initiatives, uncritically accepted by the movements in the left and right. Into this, Mandal committee report and agitations by backward communities in the 1990s outrightly projected the existence of a fundamental divide between different caste conglomerations.

It showed that the caste system, which is supposed to disappear automatically through Nehruvian secular-development policies, is still the basic structuring module of Indian society. As many social scientists point out, the Mandal agitations split the Indian campuses into two factions. This ‘democratic rupture’ significantly paved the way for the entry of backward caste communities into the academic Agraharas.

A slow but steady increase in the number of students from backward communities led student politics in new directions. Day to day atrocities in the villages gradually set foot in the elite dens. The formation of the Ambedkar Students Association in HCU and DABMSA in EFLU have to be located in this particular context. It certainly created troubles for the ruling elites and they began to persecute the students from marginalized communities through ‘glass ceilings of merit’. Lack of proper institutional mechanisms to change their inherent caste-hierarchy made affirmative actions futile.

In principle, universities have adopted inclusive policies but the space remained the centres of elite desires and ‘meritorious bodies’. Therefore, the dropout ratio among marginalised communities is many times higher than among the others. The Sukhadeo Thorat Committee report sheds light on the differential treatment meted out to students from SC-ST backgrounds. Thorat called our attention to the caste discriminations in the labs and hostels of AIIMS and IITs.

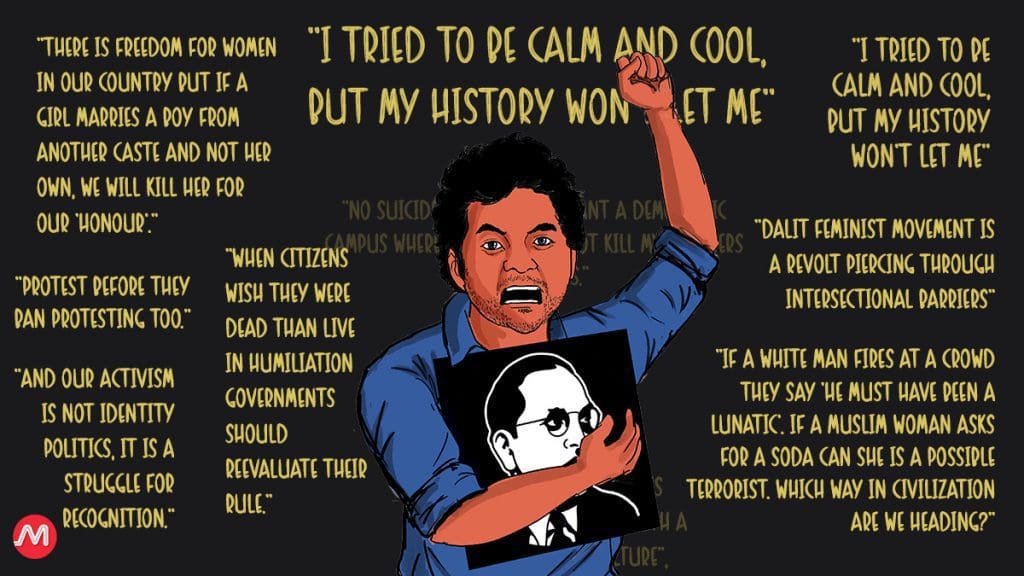

Resisting these kinds of caste domination, the subaltern students movements asserted their identities and cultures. Where upper caste surnames are ‘natural’ and ‘pleasant’ sights, these assertions were branded as ‘problematic’ and ‘hideous’. As Rohith would say, “they tried to remain calm and cool, but their history won’t let them”. Cultural assertions through Beef fests and Asura week challenged the elite fantasies. Ambedkar has resurfaced as an inspirational icon in the campuses like HCU and EFLU.

Muslims are coming!

The increase in the number of Muslim students in the central universities after the implementation of the OBC reservation in higher educational institutions produced different visual signifiers and concerns. Muslim students were not outside the purview of exclusions. The religiosity of Muslim students was always questioned and Muslim women scholars had specifically faced discriminatory approaches in the labs. As the epistemic foundation of the University hasn’t changed, Muslim students were forced to ‘discipline’ their research topics.

‘Communal’ has emerged as a tagline to address the Muslim students, to the extent that professors wrote letters to the admission committee to reject their probable admissions. The suicide of Kashmiri Muslim student Mudassir Kamran after administrative and police high handling and the protests has sparked Muslim questions in the academic spaces.

‘Muslim religiosity’ tended to puncture not only the Hindu ethos but the liberal-secular ethos as well. The formation of the Students Islamic Organisation (SIO) and Muslim Students Federation (MSF) and their conscious detachment from the secular narratives of the left movement and attachment with anti-caste politics produced debates on the potential of religion and theology in enhancing liberation and emancipation.

Dalit student leaders frequented the Muslim organizational events and vice versa, leading to a mutual process of learning and unlearning. Along with Phule, Ambedkar, Savitribai and Ayyankali, Malcolm X, Fatima Sheikh and Ali Musliar were part of the slogans, while apart from the ideas of Iqbal, Maudoodi and Jinnah, ideas of Ali Shariati, Talal Asad and Sabah Mahmood have become the talk of the campus. However, the mainstream left movements continued to show indifference to these questions of caste, community and religion.

It would not be wrong to say that this gave a new impetus to the subaltern students politics. The alliance between different marginalized groups shifted the electoral dynamics as well. In 2014, the United Democratic Alliance (UDA), an umbrella of various subaltern movements could win the students union elections in HCU. It should be noted that students from places like North-East and Kashmir were also ready to stand with this politics. Consequently, the questions of state repression and AFSPA were brought into the discussions. At this juncture, MHRD and UGC sought measures to curb the ‘radicalisation and anti-national activities in the campuses’.

Recentering Velivada

It is in the above-detailed context that we need to understand the demise of Rohith Vemula and the subsequent rise of student politics in Indian campuses. After being unjustly suspended by the administration, Rohith and the other 4 Dalit students had to live in the open space of the campus. It was Rohit Vemula who called it “Velivada” (Dalit ghetto). In the architecture of caste, ghettos used to be in the peripheries. As Susie Tharu pointed out, the replacement of the Velivada in the centre of campus is phenomenal. Thus, it brings the concerns, questions and assertions of outcastes into the centre of academic space. The meaning also shifts, from being a space of enforced slavery to a space of assertion.

Temporally, protests in other institutes like FTTI and JNU coincided with the Rohith Vemula movement. Thus, as one ASA member reminded, the anti-caste movement for the first time united with the students’ movement. Rohith’s incisive and emotive letter clearly helped, the otherwise unconscious, student community to raise up. Like the recentering of Velivada, Rohith Vemula Movement could successfully bring the anti-caste ethos into the student movement that had all these years evaded the caste question. Blue flags and Ambedkar portraits became a common sight than a rare sight.

Units of ASA were sprouted in other campuses across India. Not only the left but the Sangh Parivar also inquisitively projected a ‘friendly Ambedkar’.

However, when the glittering faded away, the anti-caste proliferations quickly lost their enthusiasm, if not vanished away. The abrupt closure and withdrawal of anti-caste questions from the mainstream are facilitated not only through suppressions but also through appropriations.

While police cases, show cause notices and banning democratic protests are the oppressive realm, the formation of Seva Lal Vidyarthi Dal by ABVP is the realm of appropriation. The glass ceilings are back in place. The slogans of ‘Jai Bhim-Lal Salam’ is fading.

Moving Caste (from) Body

Rohit Vemula is the son of Radhika Vemula who belongs to Scheduled Caste (Mala) and Mani Kumar who belongs to OBC (Vadera). The caste question is complicated by the fact that Radhika Vemula, who was abandoned by her parents at a very young age, is the adopted daughter of Anjani Devi, who belongs to the Vadera caste. Further complicating, there is no documentary evidence for adoption that will satisfy the legality of the Indian nation. Then, what can be the caste of Rohith Vemula? Roopanwala commission has declared that Rohith is not SC. Caste being an ascribed identity, who is authorised to determine it? Is one’s caste an ontic reality and determined entirely at birth? Or does experience play a role? Maybe a better question, as Satyanarayana asks, would be how to get out of this caste policing.

Indian nation-state and its legalities sustain communities through modern symbols. It is not possible to have a dignified existence without numerous legal documents. Often the identities are marked externally that self turns out to be a mere mirror reflection. The legal caste of Rohit Vemula is still in the courtroom. If a move has to be made from identity to recognition and dignity, communities have to challenge the caste policing and probably move outside the ‘caste-body’.

Such an effort requires reimagining identity and community from the vantage point of anti-caste politics. When caste groups are integrated into the ‘inclusive Hindu-whole’, a conscious departure away from the fold will move the caste (away from) body.

Thahir Jamal Kiliyamannil is a visiting PhD Research Fellow at the Centre for Modern Indian Studies (CeMIS), Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. He writes on Religion, Identity, State, and Muslims.