A few days back I was at Azim Premji University (APU), Bangalore in order to attend an event organized by Dalit-Bahujan students from the Savitri Ambedkar Cultural club. During the conversation after the event, they shared with me their experiences in APU, their political understandings and their individual journeys. Most of them were first-generation university learners.

During the discussions, there were four important points which were reiterated and I would like to mention them briefly in order to elaborate on the challenges Dalit-Bahujan students face and the conditions which can enable them to have a confident and enriching student life in higher education spaces.

There are quite a few news articles on the non-implementation of reservations, the hierarchical nature of funding and the history of higher education by Nidhin Donald, documentaries by Anoop Kumar on extreme cases of caste-based harassment of Dalit students, the inegalitarianism in social sciences and sociology in India pointed out by Gopal Guru and Vivek Kumar respectively and a critical appraisal about the nature of scholarship on caste in history by Satyanarayana, Rawat, Jangam Chinnaiah, Gajendran Ayatthurai, Gail Omvedt, G Aloysius and so on.

While these are very crucial and need to be further researched, the scope of this article is to reflect on the four points I gathered in APU and connect them with the experiences of Dalit-Bahujan students in other higher educational institutions.

The primary concern they raised in their academic life was the difficulty they faced while articulating their thoughts, observations and analysis in English. They felt that upper caste students who were not so well versed with certain topics would confidently speak generic points and that it was English which provided them with confidence. Furthermore, they told me that some of these upper-caste students would give stares and subtly make faces while they tried to make their points.

However, they also expressed a sense of security for having few faculty members who according to them were favourable to them. mentored them in academic writing and they could reach out whenever they needed. I know these faculty members in a personal capacity. Not only have they engaged in writing anti-caste content and being part of the anti-caste movement for quite some time, but also are sensible to not allow the Guru-Shishya Parampara and elitist bias one come across in Indian universities. Such practices are known to adversely affect the Dalit-Bahujan student life through negligence and discrimination, which although not always expressed in the language of caste tends to reinforce the caste distance Dalit-Bahujan students encounter growing up in society.

Given most of them were from financially struggling family backgrounds, they were relieved that the university scholarship covered their costs and they did not have to keep worrying about it. Lastly, they operated with a strong bond of community, making plans, having dinner together, sitting in the canteen and having discussions.

This however doesn’t mean supporting the privatisation of education or the kind of academic training APU and many other private universities attempt to inculcate in order to produce development sector and NGO workers as I was told. We are well aware that in the privatisation of higher education, Dalit-Bahujan students stand to lose the most. Many private universities particularly in the field of liberal arts and humanities, such as Flames, Ashoka and Jindal etc tend to be exclusive luxury resorts and launch pads for elite upper caste students to further their careers in the global market through the various MOUs and tie-ups with foreign universities, big names from academia in their advisory boards and a huge amount of money invested in their training.

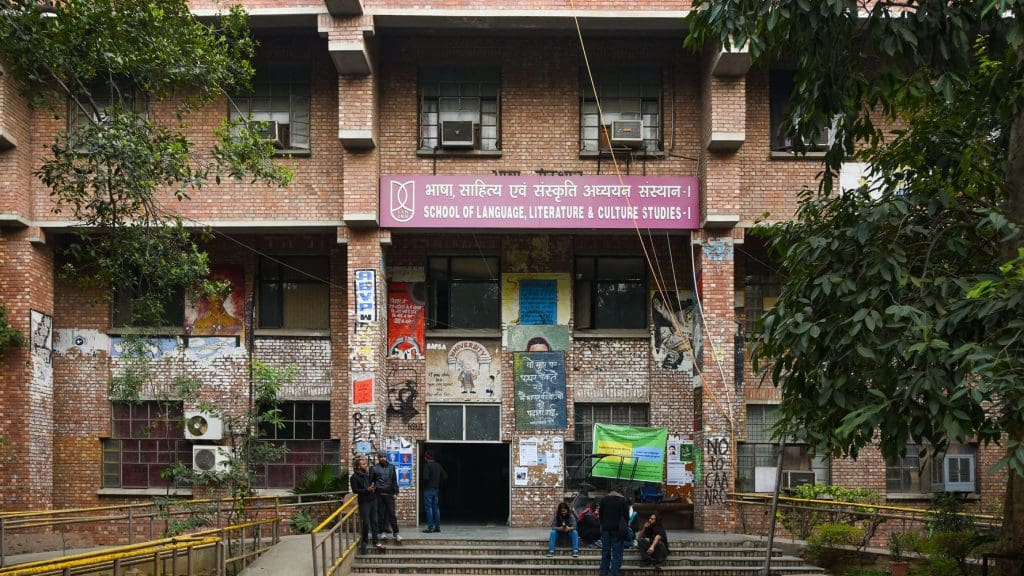

Amidst this fort of exclusivity, English can still act as a source of confidence and access to certain opportunities, exams, writings, and spaces which would otherwise be denied to Dalit-Bahujan students. This works quite differently than the mass-based popular anti-caste politics where vernacular languages spoken by Dalit-Bahujan communities play a crucial role in conscentizing and mobilizing them by cadres, writers, artists, filmmakers and political leaders. The turn to English in higher education space I argue should not be looked at as moving away from the vernacular, popular and the mass. The best example in recent time I can think of is that of Nirvedya, a vernacular anti-caste media platform in Odisha which is run by Dalit-Bahujan students from Odisha who completed their PhDs and Mphils in the English language in JNU and HCU and are working in Odisha. They have successfully been able to navigate both worlds as part of the anti-caste movement, academic life and job opportunities.

It is important to remember Nalanda academy and the training it has been providing Dalit-Bahujan students in a similar direction by empowering them through English before they enter the gates of universities.

The second point about support from faculty members is really important when it comes to Dalit-Bahujan students who navigate academic life and university spaces for the first time entangled by many questions, anxieties and apprehensions. Many a time even senior students can play the role of support system for Dalit-Bahujan students. Professor Jangam Chinnaiah who studied at JNU in the mid-1990s, in one of his articles wrote that the presence of some senior Dalit students and faculty members acted as a support system as well as channels of knowledge exchange on the anti-caste movement. Professor K Y Ratnam, Sukumar Narayana, Hany Babu, Jenny Rowena, Kancha Illiah, Vara Prasad, Sona Jharia Minz, Brahma Prakash, Sharad Baviskar, Somya Brata, Sowmya Dechhamma, Asim, Sukhdeo Thorat are few names that come to my mind who have actively supported, mentored and guided Dalit-Bahujan students in their university lives and continue to do so. Many of us have gained intellectually from them as well as seen them articulating our problems and concerns on public platforms. Such actions have boosted the Dalit-Bahujan students in crisis and as support systems to look up to. However, one needs to keep in mind that Dalit-Bahujan faculties too have been targeted and alienated and there are also faculties who do not associate with Dalit-Bahujan students due to the fear of being marked out and stigmatized based on association with caste members. Seemingly progressive writing and posturing on caste by most upper caste faculties doesn’t always end up in standing up for the Dalit-Bahujan students in universities.

The third point is about financial security and it can ease up a Dalit-Bahujan student’s life in many ways and also end up supporting the lives of those related to the student. There are many instances of Dalit research scholars in JNU who would support their younger brother and sister’s higher education through the research fellowship they received and through that they could complete their masters. There are those who saved money to build their houses, pay the hospital bills of their sick parents and conduct the weddings of their siblings. It is also interesting to note that Ambedkarite student organisations in HCU and JNU have been running for years with contributions from research fellowships by many students. Most importantly, financial security can allow a student to not take up part-time jobs, not drop studies in between and not affect their studies. It can enable them to study with peace of mind without being worried about the pressures and obligations of sustaining oneself.

As the saying goes, “Birds of a feather flock together”. In any university or college in India, sections of upper caste students tend to draw towards each other and form groups based on similar tastes, preferences, cultural markers or simply for belonging to the same caste. In colleges and universities of Meerut, this can be Jats and Gujjars trying to form caste blocs during elections with their goondaism.

At the same time, in a college like St Stephens, LSR and Miranda House, it would be the cultural elites among Syrian Christians, Punjabi Khatris, Aroras, Bengali Brahmins, Nairs and Tamil Brahmins flocking together by breaking their linguistic and regional differences in their drama society, debating society and clubs etc. The intensity of separation in socialising can vary but it persists. In such an atmosphere, Dalit-Bahujan student having their own groups can act as spaces to address individual and collective problems, stand for each other when needed and be a kind of force which would be a reminder to other students not to mistreat and take them for granted. These groups can serve other functions such as study circles, cultural activities, friend circles, and demand democratization and redressal wherever required in these spaces.

The above-mentioned list of challenges and possibilities for Dalit-Bahujan students in higher education is not exhaustive, but an attempt to shed light on certain recurring situations which are prevalent across higher education institutions in India.

Sumeet Samos is an author and anti-caste student leader. Samos has recently completed MSc in Modern South Asian Studies at Oxford.