On 9 June 2020, the Baghjan oil well in Assam’s Tinsukia district caught fire. Locals say that signs of an impending oil spill were clear – the well had been releasing gas and particulate matter into the air for two weeks before the actual leak.

When the spill inevitably happened, it burned several houses, displacing at least 1600 families; destroyed several hectares of cropland; ruined the breeding ground of several endangered species of birds; and killed many species of reptiles, insects, fish and plants in the adjacent Maguri Motapung Beel wetland (a Gangetic dolphin turned up on land, with its skin peeled off). Due to the fire, the grasslands of the nearby Dibru-Saikhowa national park have also begun drying up. Failing to contain the initial blowout, the state authorities called in specialized personnel from Singapore who managed to contain the fire, but the loss of lives and livelihoods was already beyond repair.

The Baghjan oil well is owned by Oil India Limited, which has a notorious reputation amongst environmental activists for failing to abide by government permissions. In spite of not obtaining clearance to install pipelines under the MaguriBeel, OIL went ahead with putting the pipes in. There was no Environment Impact Assessment for the Baghjan oil well, activists say.

Not only oil but forests and water are precious natural resources found in the eight states comprising India’s North-east. Nearly all post-colonial countries, in pursuit of accelerated revenue generation, foreign investment, modernization, and to scale up the ranks in global politics, have been scrambling to fully exploit their nations’ bounteous resources. This process of ‘development’, as they claim, holds as a promised future (for some more than others in these nations) environmental degradation, loss of land and livelihood, and increasing economic and social inequality.

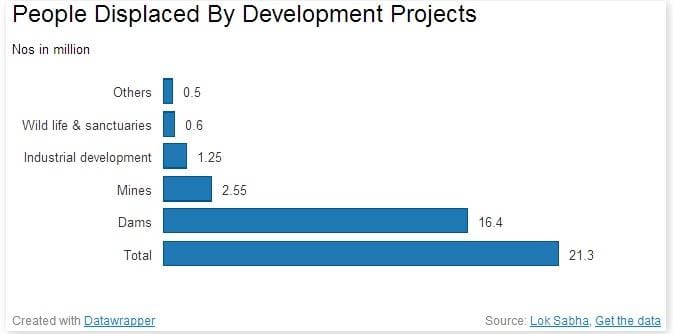

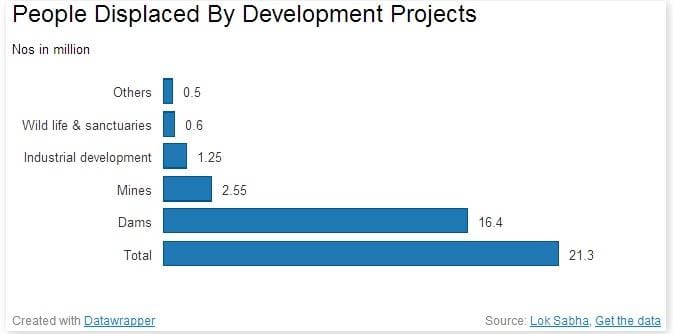

Building dams was crucial to the Nehruvian economic vision that India adopted after independence, with Nehru himself famously hailing dams as the temples of modern India. But as in temples, it is assured even with development that certain communities will be kept out of it. In his book “Interrogating Development: State, Displacement and Popular Resistance”, Prof.Monirul Hussain reveals that over the last 50 years, 3300 big dams have been built in India. Tribal people constitute 40-50% of Internally Displaced people due to dam-building. The total number of displaced people is anywhere between 33-50 million.

The highest concentration of dams is found in tribal belts such as North-East India, Narmada Valley across Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Given the lack of adequate representation of tribal interests at the higher executive and legislative levels, public and private enterprises, it is no surprise that tribal areas are the main targets of this corrosive development attack, exposing India’s development projects to be little more than casteist, Brahminical experiments to oppress communities and societies that have different traditions of ordering society, and have successfully harbored a self-sufficient relationship with their local ecology.

The fact that from the 1950s till now, every government at the center, whether it had a ‘secular’ or hardline Hindutva image, has remained consistent and unambiguous in at least their pro-dam stance, additionally coupled with their brazen refusal to provide relief and rehabilitation to the millions of people who have suffered due to these development projects, discloses the staggering lack of imagination plaguing most parts of the political spectrum regarding sustainable ways of including fringe groups of tribals into the economic and social make-up of India, instead of capturing their land and siphoning their rightful resources away from them.

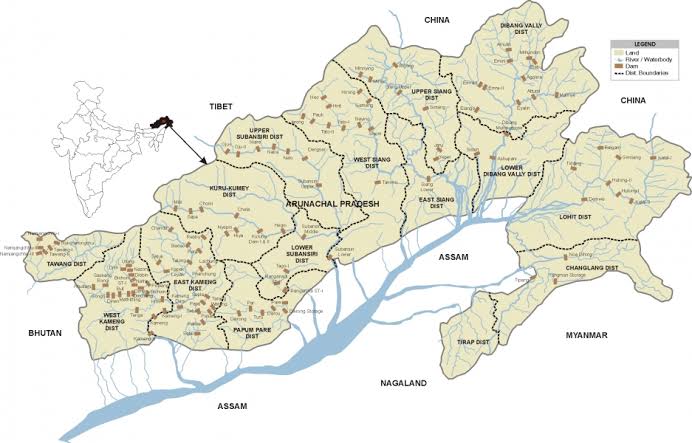

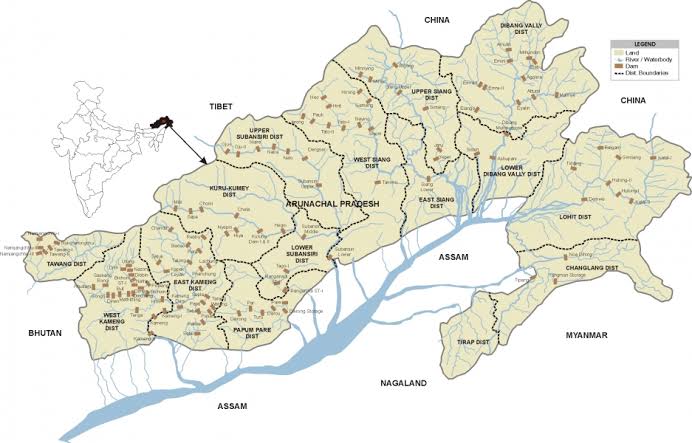

The latest assault on the rights and resources of indigenous people in the North-East comes as an aggressive push for building the 3097 MW Etalin Hydropower project in Dibang Valley in Arunachal Pradesh. This project is a joint venture between Jindal Power Limited and Arunachal Pradesh Hydro-power Development Corporation. The dam is to be constructed by felling 2.7 lakh trees and clearing 1165 hectares of forest area teeming with biodiversity. A Wildlife Institute of India (WII) study has documented 413 plants, 159 butterflies, 113 spiders, 14 amphibian, 31 reptile, 230 bird, and 21 mammalian species within the project area. Dibang Wildlife Sanctuary 12 km away has recorded a tiger presence in the vicinity.

A factsheet considered by the Forest Advisory Committee states an (obviously lowered) estimate of 95 families having to be displaced due to the dam, but admits that the state government is yet to devise a plan for their rehabilitation. The report itself states, “The land in which the project is proposed is in pristine forests with riverine growth that once cut cannot be replaced.”

If constructed, this dam will be the biggest ever in India. Its ramifications on a region so ecologically sensitive, are both disastrous and obvious. The proposed dam site is a seismically active zone and has recorded at least 34 earthquakes (seven with magnitude greater than 3 on the Richter scale) in the past century. Scientists and independent researchers have foreboded that this project poses an irreversible threat not only to the precious biodiversity of the region but to the livelihoods and community of Idu Mishmi people who have protected and managed these forests for generations.

Neither the profit-hungry governmental aspirations nor the existential threat to tribals inevitable in a dam-building enterprise is new to the history of the North-East. The notorious Subansiri dam project in Arunachal Pradesh has become over the last three decades rallying ground for local activists, common people, and political leaders against big development projects imposed upon marginalized lands and lives.

This dam was proposed to be built in 1955 by Brahmaputra Board as part of a flood-control program and was handed over in 2000 to National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) without proper scientific assessment about whether the dam would be viable to the local ecology. All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and Krishi Mukti Sangharsh Samiti (KMSS), the latter led by Akhil Gogoi, decided to campaign furiously against this.

One lakh people were badly affected in Assam, due to a flash flood caused by the Ranganadi dam in Arunachal Pradesh, in 2008. In December 2011, a group of more than 3000 activists and common people crowded up Lakhimpur district in Assam and managed to blockade a road through which materials for constructingSubansiri dam were being transported. NHPC and the government with only an illusory interest in heeding to people’s concerns kept ensnaring activists in a cumbersome chain of talks but went ahead withSubansiri dam construction anyway.

Coalitions of resistance by local people have proven to be long-lasting, tireless endeavors to strengthen the grassroots struggle against big development. The Narmada Bachao Andolan, led by Medha Patkar for over 35 years now, is testimony to this. However, the structural power imbalance hindering organic movements from being able to bring about deep changes in the top-down structure of development was best described when Akhil Gogoi termed this resistance of the peasants and local people as an “anti-imperialist” struggle.

The depth of this statement resonates in the present reality of India: that those at the center of the mainland (in terms of historically concentrated economic, social and cultural privilege) cannot enjoy and glorify their freedom without sustaining as the foundation of this freedom the continued oppression of communities at the very fringes. Seizing people’s land and resources, crushing their aspirations to autonomy, structurally disadvantaging them to preserve their heritage and history, valuing their lives at a lesser cost than others, are deliberate strategies adopted by Indian governments that have alienated and disillusioned these communities, who for the same reasons, reject the beckoning of ‘inclusion’ from India.

The Ranganadi dam in Arunachal Pradesh has a similar past and future of woes. On 9 February, heavy silt deposits were found in the water of Ranganadiriver, a tributary of the Brahmaputra. People living in villages along the course of the river found several dead fish floating on its surface. This dam which belongs to North Eastern Electric Power Corporation (NEEPCO), is perceived by the locals as the “government’s curse upon them”. They complain that the dam causes heavy flooding in monsoon season and dries up the river in winters. Farming has proven to be extremely difficult for them in such precarious conditions.

One can easily imagine the chain of setbacks caused by successive, yearly floods in societies relying on the hope of a good annual harvest. Most of the young, able-bodied men from areas around Ranganadiriver have migrated to other places in search of livelihoods, leaving women to deal with the problems caused by the dam. They now live in the impending fear of their houses being washed away due to overflooding, every monsoon season.

In a notice, NEEPCO claimed that it will ‘not take any responsibility for any loss/damage to life and property, etc. in case of any accident owing to violation of the notice.’ This lack of accountability is a hallmark aspect of the attitude that supports the unplanned proliferation of dams.

The history of the Khuga dam in Mata village of Manipur is rife with failure and corruption. The central government led by the Congress, commissioned 433 crores for the building of this dam, promising to generate 1.5 MW of hydro-power, and provide 5 million gallons of water per day for the use of various communities in Churachandpur and Bishenpur districts. Its present reality however is bleak. Not only has it failed to generate a single unit of electricity to the benefit of locals, due to repeated multiple canal breaches and overflows, but it has also displaced hundreds of families living in villages surrounding the dam. It has served to create only an artificial lake for ‘beautification’ purposes which serves as a tourist spot.

Locals ask why the dam was created when it has no functional use whatsoever, alleging that their lifestyle was prosperous and self-dependent before the dam was created. Now that they have lost their land and had to disperse to other areas, unemployment is rampant amongst these communities as they are struggling to find alternate sources of livelihood. They are forced to travel long distances to obtain potable water since their regular supply of water from the free-flowing river has been disrupted and dam water is not fit for consumption.

Many civilians’ lives have been lost due to drowning, as boats and canoes have capsized in the unstable waters of the dam channel. Three people were killed and 32 injured, as the local police, 12th Indian Reserve Battalion, and BSF officers opened fire on locals protesting against this unjust seizure of their land and resources, which has impoverished their lives.

The Khuga dam too needs to be seen as an example of thoughtless squandering of public money, and forceful erosion of marginalized farmers’ autonomy over their ancient means of sustenance: a claim of autonomy so seemingly disruptive to the faux democratic freedoms that apologists of cannibalistic Indian nationalism believe should be everyone’s share, that it needed to be silenced through the use of brute force on the ground level, and ‘objective’ dialogues of development at the higher levels of profit-minded society.

In the first week of August 2018, around 1 lakh people in Golaghat, Assam were affected by the sudden release of water from the Doyang dam in Nagaland. Neither NEEPCO nor the concerned authorities of both states had warned the locals about so that they could have enough time to save themselves and their belongings. The Golaghat region was experiencing drought-like conditions just before the dam burst, and suddenly they found their lives upturned by the flash flood. It submerged their cropping lands, farming equipment, much of their livestock cattle, and their houses.

Many people also lost their documents due to this flood and were ridden by anxiety about whether they would be included, due to no fault of their own, in the controversial National Register of Citizenship (NRC) which was to begin by the end of August. They were desperate to know if, yet convinced, the local administration would not provide them with adequate relief measures and understand their plight as ‘equal’ citizens of this country.

Having learned nothing from these very public failures, albeit rarely covered on national media in the devastating light that it deserves, the government is still pushing tirelessly for the building of Tipaimukh High Dam on the Barak river of Manipur, and the Etalin project in Dibang Valley. The government proposes to build 168 mega dams in Arunachal Pradesh. Samujjal Bhattacharya, an advisor to AASU, termed each of these mega-dams “a hydro-bomb”.

It is true that North-East people’s protests against big development projects is one of survival first and dignity later. But the government profit-machine does not take a break. Apart from military coercion to kill and silence (the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) has been vibrantly operational in North-East since five decades), state-sponsored violence is continuously cushioned and supported by the targeted vilification of North-Eastern people in media and mainland sensibility.

In the rubric of ‘New India,’ the North-East exists as a profitable but unsustainable pipeline to serve the exclusionary interests of the center. Evidently, this exercise in development is a crucial subset of a blood-stained politics carried out by an organism that has neither eyes to see nor ears to hear, it has a boastful mind and sharp teeth to tear. It colonizes histories and cultures from ancient societies and as a way of forging dependence, loans them nightmares of oblivion that they must pay off in installments. It swells with a lasting emptiness, standardizes progress, dreams and aspirations, and (lack of consideration given to) local struggle and resistance.

Sukanya Roy, an English graduate from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi, is a freelance writer based in New Delhi. She has volunteered for many collectives including the National Alliance of People’s Movements.