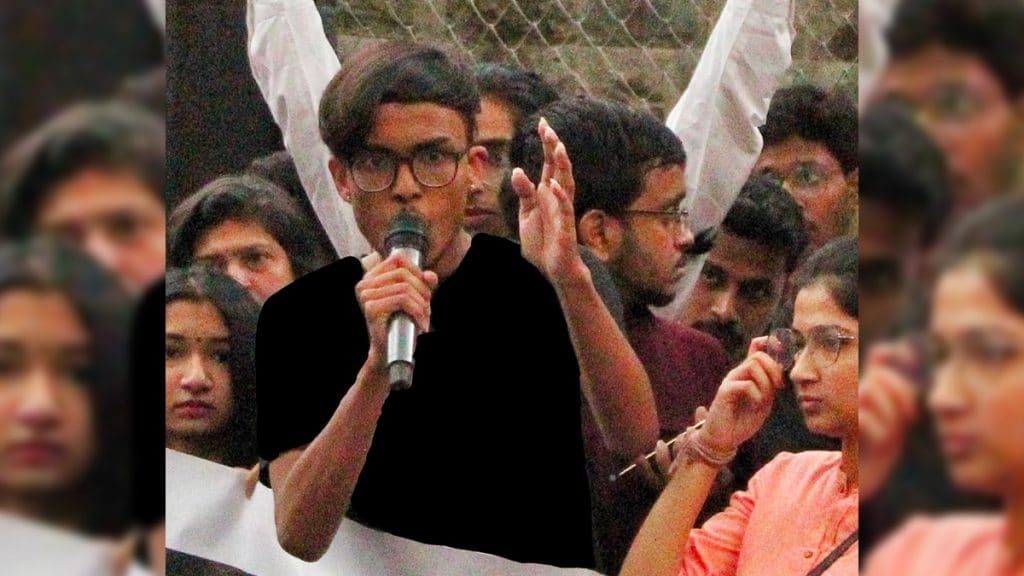

18-year-old Sankul Sonawane had no other choice but to fight it out against the casteism he was born into. Sonwane is among the new generation of Dalits who are not ready to give a free pass to any forms of segregation. He rose to become one of the most vocal anti-caste activists on social media by his sharp and articulate commentary against social injustice.

Last year, Sonawane was a speaker at Oxford Human Rights Film Festival. The Pune based student is an aspiring journalist and a writer. In January Maktoob spoke to Sonawane about his story.

Edited excerpts :

Q. What’s your story? You have been a pain for a lot of upper caste liberals for the longest time, how did your social media activism start?

A. I just say the truth of the country to be honest. If people find it uncomfortable, then I think they’ve been living in a bubble and it’s not my fault that they’ve been exposed to reality or their privilege. The harsh reality of the country is that it’s not all about Ganga-Yamuna Tehzeeb or incredible India. A large majority of the population is being oppressed by a few. And even though people think that has changed now that India is becoming more inclusive and progressive. In fact, we are not at all becoming inclusive and progressive but we are going backwards, and going towards a darker and draconian era.

Q. What made you think that you have to call out casteist people, their bigotry, hypocrisy?

A. Basically, I was born in a Maharashtrian Buddhist family, an Ambedkarite family. So as far as the movement goes, I was pretty much born into it. So in a way, it’s just something that my parents and my grandparents and our family would imbibe in me. So for me, caste wasn’t discovered on the Internet like many privileged people. It’s just something that I saw from my very own eyes from a very young age. And that’s the case for most Dalits. We don’t discover caste as a hashtag or as a movement or a trend on social media. We are born into it. It was the same story for me.

The people who are on Instagram, on social media, see things and they ask themselves, Is this really casteist? They don’t question themselves, double question themselves. For us, it’s not just that.

I just saw things from a very young age and I could recognize that there is caste in this, there is caste in that. And it did not take me very long because, all of the circumstances that we are born into, the kind of place that we grew up in, the kind of school that we go to. For us, it’s everywhere. The kind of jobs we do, the kind of jobs our parents do, our family history, where we come from.

All of these things taught me about caste more than a book or a social media movement or anything like that ever could. And as far as the shift to social media comes, and since I was pretty much born into it and had affected me from a very young age, the outrage on social media just came naturally. The Rohit Vemula movement, the SC-ST act being modified, pretty much revoked, these movements that I have been part of as a kid, even though I was not on social media back then.

So I was a part of the anti-caste movement before I got on Twitter and Instagram. I could see that social media was a very upper-caste dominated space, a casteist space. Especially when you go back to a few years when it was not as accessible.

So the majority of the people who were on social media were upper-caste and the kind of casteism that was happening around was pretty much normal. At least now you could say that we have anti-caste accounts and Bahujan People, Dalit people calling out these kinds of casteism. But a few years ago, that was not the case. So for me, the anti-caste activism online started from a feeling of isolation because there was rampant casteism happening around which went completely unchecked.

So, when I felt like I have a space and this blatant casteism should be called out because this is not something that we should be living with anymore. We already face taunts, insults, and casteist jibes every day in real life. So, at least on the internet, it should not be something that is tolerated.

Q. What do you think about the current realpolitik scenario? Are we going forward? Is casteism vanishing?

A. I feel like it’s getting more and more brazen, to be honest. In this day and age, the kind of casteist atrocities that are happening, what happened in Hathras is not a one-time incident, It happens every single day. The only difference is that it doesn’t get the same kind of outrage every day.

The thing with statistics is that they just kind of reduce the horror of the atrocity. When you say that every 15 minutes a crime happens against the Dalit. By the time we’re done with this call, there will be atrocities happening against Dalits around the country. But when you reduce that to a statistic, it is normalised.

And people don’t actually come to know about the horror behind every single atrocity that happens against the Dalit. And these statistics are just something that at this point, we have begun to make invisible and to just look the other way because this country does not prioritise fixing the problem of caste. You don’t see an election campaign or an election manifesto that talks about eradicating caste. You don’t talk about eradicating, making the atrocity act stronger or giving stronger punishment for the upper caste people because that doesn’t go along with the political agendas of the parties, no matter which side of the spectrum they come from. So not only is this kind of atrocity being normalised but it’s also being looked at the other way by both political parties and common people. This is not something that should be normalised.

When something like this happens abroad, in a different country, it does become the talking point or something that has to be taken up immediately. But here it’s silenced. It’s normalised. It’s looked at the other way. People try to suppress it as much as possible. And that just turns into a kind of, one atrocity after the other. It’s like a momentum that keeps happening and it keeps happening again and again. It’s like a cycle of Dalit atrocities that happen. And then once again, it just keeps going on and on till a point where something like Hathras happens and people are like, enough is enough. This is something that must be called out.

Another unique thing about Dalit atrocities that happen is that I’m sorry to say this, but most of the people who protest against this kind of atrocities at the end of the day are still Dalits.

I’ve never seen another caste person come to a movement like the Rohit Vemula movement or SC-ST act movement or any movement may it be, even Bhima-Koregaon. I go to Bhima – Koregaon, every single year and never see upper caste people. Because for them the most activism they will do; the younger generation will go on social media and create a hashtag.

That’s the most they would be engaging and they would want to engage beyond that. So at the end of the day, even when you talk about atrocities that happen in India, first of all, the state and the government do their absolute utmost capacity to suppress it, to hide, to quash any kind of anger or any kind of protest that comes out of it. And on the other side, you have only the Dalits who are protesting against this. So, the upper caste people who are in a way responsible for this will never come out and protest it, let alone try to fix it.

Q. What are your thoughts on the EWS Reservation and itz impact on the already established system and quotas of resevation?

A. Reservation was to provide representation for those who have been historically marginalised. The whole point of reservation in education and jobs is to give an opportunity to those who have not been given education and jobs. But when you introduce something like the EWS as the economically weaker section reservation, you have to look at who is actually gaining from this EWS. First of all, the actual people who are poor in this country, the Dalits, Adivasis, the OBC’s, the Muslims, the SC-ST are not allowed to get reservations- they are barred from it. So it is only for those who are from the open category, the upper caste category. Now within this, you have an income limit of eight lakhs which, by the way, is the same limit that you have for OBC’s. So this just raises a very interesting question. And also a very stupid question. Are upper castes and OBC’s on the same platform?

Are they being oppressed the same? No. Then why do they have the same kind of criteria for both of these? And then again, it goes on to show that people who are in favour of EWS never bother to question the income limit, which is 8 lakhs.

What kind of a poor person, even a middle-class person earns around 60000 – 70000 per month. Now that is when you are creating this absurd idea of EWS reservation. It is crafted, tailor-made to benefit those who are already privileged. So it is a reservation for the privileged. There is no point in calling it a reservation, you might as well just call it an excerpt from the manusmriti.

Q. The Upper castes have always blamed reservation for the losses that India has incurred in the field of sports, arts, culture, etc. The campaign of blame is still ongoing. Why do you think India still allows it?

A. To give you an answer in a very simple manner, it’s because Dalits, OBC’s and Adivasis are an easy targets. Because we don’t have any, I’m sorry to say this, but we don’t have any representation, anywhere at all. We don’t have any representation in the media, film, or sports.

So, you can pass this as like a popular narrative because none of us is being given a mic to speak at all. We are not included in the popular mainstream narrative at all. Let’s say you invite us to a debate, it’s like not giving us a mic at all and you give the other side like a bunch of loudspeakers because of course, they’re going to yell whatever they want. But if we don’t have it, we won’t be able to raise our point at all. Reservation generally boils down to the fact that because for Savarnas It’s a very easy thing for them to blame.

No matter what happens in that life, tomorrow they can shove their toe against the table and they will still blame reservations. And they still find it completely logical to do that because they’ve been raised in an ecosystem or circle, where it’s normal to do this kind of narrative, to have this kind of hatred for lower-class people and Muslims. When you look at the youth especially. People often consider the youth to be the future, that they will lead us towards a progressive India. But every day you go on Twitter you see the kind of hate that these young people are spewing against Dalits, Muslims, especially Muslim women. It was turning into a whole trend. It just shows you and it’s not like a lone wolf. it’s an entire demographic which is being radicalised, which is being filled with such kind of hatred. And this hatred goes for anyone who’s already marginalised because the privileged people in this country have not been taught to accept their own shortcomings. Instead, they have been taught that whatever is happening in this country is because of Dalits, Muslims, Reservation, whatever it may be. So, continuing the conversation of representation, you have representation abroad, in different countries. You have representation in private sectors, in film, you have representation in sports even.

Recently, India lost a test series to South Africa. South Africa has a reservation in their cricket team. And it’s worked out well because there, the players who are called quota players have come out and they perform brilliantly. And this would not have happened in South African cricket 10. 20 years ago because the black players in their team were victims of rampant racism. But the government decided to fix that problem to ensure representation. But here the question of representation is not even being asked, the question of representation for Dalits in sports, Dalits in media, Dalits in whichever spirit maybe. Even for Muslims, the Pashmanda Muslims. It’s not even something that is on the table for us right now. We’re not even willing to discuss it. So, when the discussion is about ending reservation at a time when the minorities and the backward classes are already going through so much. It just raises the point that where are we as a country going on, it’s not forwards for sure.

Q. The Upper Caste people have been trying to form/express their solidarity through sitting and eating with Dalits. What’s wrong with such solidarities?

A. Well you have to ask yourself what year it is first of all. The year is 2022.

It’s not the 17th century or the 18th century. It’s 75 years after independence, and we are still trying to do this kind of act where we are trying to sit and eat with Dalits. It just kind of makes you ask yourself, how is this normalised? How is this in a way acceptable at all to begin with? If you go anywhere else, what kind of a privileged person or a person from an oppressor population comes towards a backwards or a minority person and captures a photo of eating food with them? On one hand, you talk about erasing reservations. On the other hand, you want to eat food with Dalits and try to normalise that. Then it just shows you that this is a big disparity. There’s a big dichotomy, it’s like black and white. You are on one hand, trying to claim that all upper castes are the oppressed ones, Dalits are having fancy jobs, government jobs and already held by reservation. But on the other hand, you are trying to normalise eating with a Dalit as a big deal.

So then where are we as a country heading? It is 2022 and we still are doing this act of eating and sitting with Dalits. These things are still not acceptable. Yogi might be doing it. But at the same time, in his own home state of U.P, there are Dalits being killed for eating with an upper caste person. It’s absolutely absurd. Dalits are even oppressed for these kinds of basic acts, for eating food with an upper-caste or riding a horse.

This points to how far we are to achieve as a country. Even though we’ve hit 75 years of independence, and even though we have a constitution that is meant to provide equality for all and reservation, all of these constitutional safeguards that we have in place. The on ground reality is completely different because the on ground realities that you’re still trying to figure out how to make Dalits and Upper Caste sit together because the upper caste might attack the Dalit person for just eating with them.

And it’s a very big difference that goes on between what people on Twitter claim about what the status of Dalit is and the actual status of Dalit in the villages or the cities.

Q. Dalits have been discriminated against and forced to bear the brunt of injustice in University spaces. How is your experience as a Dalit on campus?

A. See, as someone who studies in college you have to ask what is the situation of Dalits in universities. You have to look at the chancellors, the vice-chancellors, the teachers, the professors. Statistics will show you how much lack of representation of the Dalit and Bahujan professors are there in universities? Forget about a Dalit or a Bahujan becoming head of a university. That is a long, long dream for us.

In central universities and government colleges, there is a constitutional safeguard for a certain number of teachers to be SC-ST’s, OBC’s, because that is according to the reservation that has been given to us by the Constitution.

And yet these seats themselves are not filled. So what happens in universities is that there is an overwhelming amount of upper caste professors and these professors have come from a childhood where they themselves have been taught to blame Dalits for everything.

So that turns into an entire cycle of casteism that goes on from one generation to another generation. So when the teachers themselves are not going to treat the students fairly or equally, then you can’t expect universities to be a safe space or to be an equal space.

And of course, casteism is rampant in universities because it is being approved from the top. It is not the case that one student passes a casteist joke. Things are much more serious and rooted. In some of the universities in Pune, there are separate lines for Dalit students, Bahujan students and Upper caste students. That is a very straightforward form of segregation, and there is no other way to justify it or to defend it. The moment you enter college, you are being segregated like it was in 1960s South Africa. You are living in an apartheid era. And from then on, when you have professors or universities who are approving this kind of segregation, the students standing in the Dalit or Bahujan line, they are going to see themselves as easy targets then. And that tag of being a Dalit or Bahujan. It is a very high price to pay in Universities. Be it for 3 years, 5 years, how long their courses.The upper caste students are going to target you because of the kind of environment they grew up in they have been taught in a way that we are responsible for every single failure or every single unfortunate thing that has happened with them. You might think it’s absurd, but that is the environment that they grew up in. And then that’s the environment that they bring to the college. And they have a way to take out their frustration on Dalit students. That’s how harassment happens in colleges.

The three upper-caste doctors who are responsible for Payal Tadvi’s murder. They know they have not been punished yet. And it’s not just them. Even now, Rohit Vemula’s killers are roaming freely, it’s been six years.

Can you believe it? It’s been six years since Rohit Vemula’s death, and still there is no punishment for anyone. Smriti Irani is still on television, giving interviews to times now, and Republic, she’s doing fine. The other Chancellors and the rest of the people responsible for it, one of them has been made a governor in Haryana. Others are doing fine. They are the heads of universities and colleges. So in a way, it just gives the message that after all this outrage that was done by students mostly of Dalit – Bahujan background who have been, , suffering the same fate as the likes of Payal Tadvi and Rohit Vemula. It is a slap in the face to all of us because we have just been shown that you can protest, you can do whatever you want. It doesn’t matter, even if we kill you nothing is going to happen to us because nothing has happened to any of the people who were responsible.

At the end of the day, our Rohit Vemula has just become this person whose justice is postponed/denied. All of these people pay their tribute to him. They might pay their respect to him. But what are they doing to take action against the people who are responsible for his death?

Forget about them going to jail or facing the courts for this. They are not even questioned about this. And they have carried on with their lives normally. For us, Rohit Vemula still remains as a symbol of resistance, a symbol of courage.

Q. What are your political aspirations? What are the steps needed to significantly change society to pave a better life for Dalits?

A. I think it has to start with the oppressor. We Dalits know what our problems are, we know what is happening to us. So, it’s not that we are unaware of it or we need to be taught what is happening to us. We already know that. But, what needs to happen is acknowledging and addressing who the oppressor is here. So, it goes to show upper caste people need to acknowledge the fact that they are responsible for the casteism that is happening in this country. Even though not every single one of them is committing the crime.

So, it’s not just an isolated incident. It is society as a whole that is targeting Dalits and it is something that has to be addressed from its root cause itself.

When you look at the recent case of Sulli deals or Bulli bhai, you have to stop calling these young people lone wolves because they are growing up in that kind of an ecosystem where they have been taught to normalise hatred against Muslims. And in this similar vein, upper castes have been taught to blame Dalits, to villainize Dalits, and that is where the problem has to be corrected. That is where we have to fix as a society.

We have to fix the fact that, teaching about caste , talking about caste and teaching the right things about caste, because recently, we were being taught caste in our college and, a lot of students, their first response was what about reservation.

Why can’t we end reservations first ? So that mentality in itself is a problem because you are not focusing on the main problem. You’re focusing on something entirely that is an inconvenience to you. I would not say it’s a problem to you, but an inconvenience to you.

When that kind of a mentality is being normalised, you have to start from ground zero, you have to start from the bottom. You have to acknowledge that the very teachings of caste are not being taught properly. Of course, there is responsibility for the government to ensure more representation, to make stricter law, to take action against the accused people in the Prevention of Atrocities Act and all of these certain things as well. But I would say that given the current political scenario in this country, it’s a long shot.

But if people who are upper caste want to address the casteism in the country, the misogyny, the Islamophobia, they have to introspect and see among their own circles where this is coming from. Because, that is where you will start fixing the problem. Then of course, you can come to the fact that government laws are being passed. But even if they are passed, they have to be implemented on the ground level; the oppressor has to fix this current situation.

Q. What are your thoughts on the rampant far-right Hindu radicalization going on in the country?

A. When you talk about the current scenario in this country. It makes you wonder. This is not a situation where few people are radicalised or few people are acting out in this manner.It’s a whole group of people who are acting out in this way. Just look at some of the the kind of content that these kind of kids used to post recently about Muslim women, about Dalits.

It just goes on to show how we as a country are turning a blind eye to this problem. We are not addressing this problem the way it needs to be addressed. These are not some kids who are sitting with their computers in far off villages, these are people who are around us – people in our schools, colleges, universities, people who are all around us, living with us, working with us. And they are radicalised to the point where they have become extremists.

And this extremism is not being addressed. It is being treated as some kind of a one off incident, but it is being treated as an isolated incident. And that’s not going to help fix the problem.

When the prime minister doesn’t say something about this, it just goes on to show where their priorities are. Forget about the prime minister. Most people from the ruling party have not said anything about this. So in a way that just shows that their concern is not here.

Even the Haridwar hate speech incident, which was far more worse because you had people doing that on the ground and in a way that is, these kids, are just like a younger version of the people who are doing the Haridwar event. And when you have anchors, news anchors, so-called religious leaders who are leading this kind of an act.

And when people from the governing party are not taking any action at all;not listening at all, at the very least condemning it. It just shows that they are giving their silent support to it. That just makes things look very bleak.

Q. Why do you think saviour politics is insufficent and problematic. Why is it as bad technique of forming solidarities?

A. Because the idea of passing the mic doesn’t actually help the oppressed minority. It’s for the oppressor or upper caste people to feel good about themselves. It’s for them to have a checklist of the things they have to do in order to be a good person.

For example, one checkbox is passing the mic to a Dalit, passing it to a Muslim, passing it to a woman. And that doesn’t help anyone. Because for them they are passing the mic for that moment being when something like Hathras happens, they will post one tweet or put something on Instagram, share something on their story. But after that, they move on with their lives. For them, when they pass the mic, their quota of being a good ally is over. But, the very next day, the Dalit has to wake up as a Dalit, the Muslim has to wake up as a Muslim, whichever minority it is, whichever oppressed, marginalized community it is. They still have to face that reality everyday. Passing the mic means you’ll have to take the mic back from them the next day or the next moment.

But for the oppressed people, the movement has to be something that leads to a complete shift in the situation of the oppressed people. When you still have Dalits who are victims of atrocities, who are still not getting access to education, Dalits who are still facing casteism, be it in a village or university. For all these Dalits, change has to come everywhere. It cannot just be about passing the mic or about getting an opportunity somewhere. It has to be a cultural shift in the way we look at Dalits, in the way Dalits have a role in society. It cannot just be like inviting a Dalit to speak at an event and then moving on from there.

The Dalit cannot just come for one day and the next day you keep on with whatever is shown in your news channel. The Dalit has to be a regular panellist and not for being a Dalit but for being a panellist, for being an expert on something other than his immediate identity.

So that is the whole point. Passing the mic should not have to be to comfort the oppressor. It has to be to really bring change and bring about the movement for the oppressed.

Q. Dalits are often forced to limit themselves to their identity. What are your thoughts about this?

A. I don’t mind being called a Dalit, but I don’t want to be called only a Dalit. I have other hobbies. I have other interests. I have other aspects about me that people don’t consider. I talk about caste, I talk about politics, but that is not the only thing I am.

And that is what a lot of people fail to understand about oppression or marginalisation. Suppose I meet you outside, I wouldn’t just want to talk about politics. I would like to talk to you about anything at all, just like normal people.

But when you are reducing someone to that immediate identity, what you are doing is that you are giving them that tag in a way that they can’t be something else. And again it just goes along with the pattern of what the mainstream media does, what what, what society as a whole does. , whenever there’s a tragedy, you call a Dalit, you give him the mic. Talk about it. That’s not helping. I’m sorry.

That Dalit person apart from being a Dalit, is also something else. If there is something else happening, then you should also go to him and ask his opinion on that event. And not because of a Dalit but because of his expertise or his interest in that event, which is often not considered and needs to be considered because Dalits are not just Dalits. We are more than that. We are human beings and we have other interests, aspirations, other hobbies which also need to be considered. Because reducing us to an immediate identity is at the end of the day also casteism.

Transcription and editing by Muhammed Faiz