“A system cannot fail those it was never meant to protect” – W. E. B. Du Bois

Since India’s independence in 1947, the government has consistently pursued policies designed to mitigate the disadvantages of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. A variety of government assistance programs targeted these groups, and they benefit from reservations in educational and political institutions. Muslims (14%) make up a similar percentage of India’s population as Scheduled Castes (17%) and Scheduled Tribes (14%). Even though Muslim disadvantage has been publicly acknowledged, particularly in the well-known Sachar Committee Report (2006), there are few provisions in place to protect them and no significant political mobilisation in their favour.

In 1909, British colonial authorities granted Muslims reserved seats in legislatures and in 1926, separate electorates and a 25% quota in public service were established to match their 24 per cent demographic share.

H.V Hudson, the commissioner of reforms commission commented that in independent India, minorities particularly Muslims without political and economic safeguard will be relegated to the status of “Cinderella with trade-union rights and a radio in the kitchen but still below stairs”.

This gives us insight into the premises of colonial justification for attempting to balance the numbers of different populations in legislative bodies, other services and other spheres. This was based on twofold rationale, firstly, it was founded on the idea that India was a ‘conglomeration of communities’ rather than a country, the participation of people from various communities in legislatures and services was seen as a desirable aim in and of itself. Minority protections were therefore justified as a measure to foster political accommodation of various populations.

Secondly, they were also recognised as a tool for improving the condition of marginalised groups. However, such communal awards were also viewed with suspicion by the nationalist forces as an instrument of the colonial “divide and rule policy”, which was designed by deceitful colonial authorities to mislead minorities, cause friction amongst different sections of the nation to weaken the struggle of independence and postpone the final transfer of power and deny Indian nationhood.

Such scepticism among the nationalists who held the majority in the constituent assembly about affirmative action on a communal basis led to the erasure of such safeguards and by the final draft of the constitution, religious minorities were excluded from all political safeguards, which were largely limited to the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes.

Muslim representatives – particularly the Muslim League members – asserted that the Muslims were a nation to avoid the numerical logic. It was argued that as a community, they were doomed to being a perpetual minority in a united India but as a nation, they were entitled to equal status, irrespective of their numbers, since the family of nations includes the big and the small. Thus, should be regarded with absolute equity in all organs of the government.

However, after the partition, in the landscape of violent vivisection of the country on communal grounds and a new political reality for the congress where it no longer had to reconcile with the Muslim League.

It no longer had any real roadblock in pushing the agenda of construing secularism as state neutrality – a major concern of contemporary liberalism, leading to minority safeguards being labelled as ‘concessions’,’ privileges, and ‘crutches’. Although the Indian constitution adopted the salad bowl theory that the distinctive identity of all communities is to be cherished and celebrated, the de facto imagination of the nationalists in the constituent assembly for the future republic was similar to the melting-pot theory, where arguments for the negation of all social relations except being Indian were made.

G B Pant commented by saying; “There is the unwholesome and to some extent degrading habit of always thinking in terms of communities and never in terms of citizens. But it is after all citizens who form communities, and the individual as such is essentially the core of all mechanisms and means and devices that are adopted for securing progress and advancement. So let us remember that it is the citizens that must count. It is the citizen that forms the base as well as the summit of the social pyramid”.

These arguments asserted that it is necessary to introduce a new secular ethos for nation-building where the polity sees itself as Indian first and foremost which would eventually render all ingroup affiliations irrelevant in the political realm and thus — providing any protections on a communal basis was untenable with this goal. Meanwhile, in a post-partition reality, many Muslim representatives, such as Naziruddin Ahmad and Begum Azazul Rasul, rejected the proposal of continuing reservation for Muslims because they felt that such protections would further the distrust towards Muslims; whereas Muslim leaders like Sir Syed Saadullah and Zahir-ul-Hasan Lari who still supported the cause of minority safeguards were increasingly seen invoking the analogies where the majority was accorded the status of elder sibling and was asked to show benevolence towards younger siblings that were Muslims.

The term ‘tyranny of the majority’ was often provoked in tandem with the ‘first past the post electoral system.’ While advocating proportional representation, canons of political equality in a democracy and Mill’s fundamental principle of democracy were frequently adduced, but, with futility.

These attempts nonetheless illustrate how minority claims were restated in words that were more acceptable to the prevailing majority opinion and in language that was drawn from the nationalist vocabulary.

The second wave of demand for Muslim affirmative action came to post the implementation of the Second Backward Classes Commission, also popularly known as the Mandal Commission Report. After decades of political ghettoisation, where Muslim aspirations were articulated around their religious identity and their politics was centred around emotive issues like Urdu and personal laws, the implementation of the Mandal Commission shifted the political agenda from identity and secularism to social justice. From the speeches of Muslim intellectuals and leaders at that time, it can be inferred that this concern arose as it was increasingly felt that unless Muslims get aboard the backwardness juggernaut they will be swamped together with upper-caste Hindus to compete on dwindling number of unreserved seats in government services and educational institutes.

Muslim members of Rajya Sabha vehemently demanded that all sections of Muslims must be provided with preferential treatment in matters of public employment to which VP Singh, the then Prime Minister, responded that his government is ‘not averse’ to reserving jobs but subdued the demand by citing that it needed broader political unity as it required a constitutional amendment. This period also saw the rise of Hindutva nationalist politics with the consolidation of Hindus for Ramjanambhoomi.

The Hindutva nationalist saw the accommodative stand of secular parties concerning Muslim reservation as partisan and typecasted it as politics of ‘tushtikaran’ (appeasement) and charged Muslims with “walking in the elders’ footsteps…. going back to 1906” (referring to the foundation of the Muslim League) and “heading towards another Pakistan” for making these demands.

However, Mandalization did provide a sizable backward Muslim population with reservation on a caste basis. This has led to the democratization within the Muslim society giving rise to the terminology of ‘masavaat’ (equality) – a more systematic and rigorous critique of Ashraf’s hegemony over the Muslim social life and new political arithmetic in the form of Pasmanda politics by organisations like Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz.

As far as Muslims were concerned, the matter rested there until the release of the Sachar Committee Report in 2006. This led to the third wave of demanding affirmative action for Muslims, this sudden new demand was marked by the shifting of the principal argument for reservation from representation to marginalisation.

The findings of the Sachar Committee Report were not particularly surprising; they were already quite evident to the political activist, social scientists, and Muslim masses themselves. However, it brought about the “secularisation” of language for Muslim reservation as the Sachar Committee provided ‘hard data’ about the Muslim marginalisation.

The report analyses the Muslim question from the lens of equity, security, and identity – major concerns of any minority in a modern nation-state. In a way, it provided a base for a new kind of articulation for affirmative action among Muslims – an articulation that was phrased in a manner that was difficult to dismiss by the state and more palatable to the dominant secular opinion which we can observe for one instance in The Communist Party of India (Marxist) statement that “the Sachar Report has blown the myth of minority appeasement by presenting scientifically collated evidence”.

Even the Hindutva nationalist struggled to come up with counter-arguments and at times even co-opted by arguing that Muslims were treated as a vote bank which has led to their isolation.

L K Advani’s assessment of the Sachar report gives an insight into this argument where he said, “In setting up the Sachar Committee, the government had its objectives. But going through the comparative statistics compiled by the committee, I feel Gujarat should be grateful to Justice Sachar for proving convincingly to the country that under Narendra Bhai Modi’s regime, Muslims are far better off than their compatriots in other states” and this rhetoric further develops into a popular slogan of “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas” (development for everyone, appeasement for none).

Sachar Committee Report surprisingly churned a disillusionment among Muslims as well where there was a realisation that years of patronage of non-identitarian secular parties has resulted very less for them and it led to mushrooming of many identitarian secular parties like Peace party in Uttar Pradesh. All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) also refashioned its politics on a similar plank and its leader Assadudin Owaisi is often heard citing figures and data in public rallies to make a case of Muslim marginalisation.

The rapid expansion of AIMIM over the years after the Sachar Committee Report indicates the popularity of this ‘academic’ brand of politics in the community with slogans like ‘Apni Siyasat, Apni Qayadat’ (Our Politics, Our Leader) becoming increasingly popular. Principally, Sachar Committee Report made Muslim affirmative action into a question of citizenship, that is of providing equal status in terms of health, education and other ‘secular’ field of social life like workforce participation and labour market discrimination.

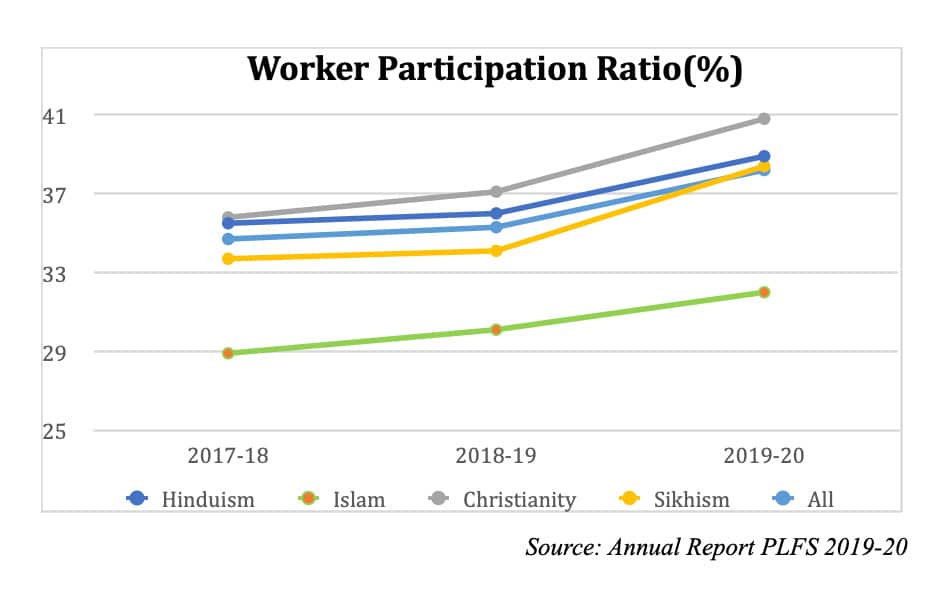

The empirical work on Muslim marginalisation and how lack of affirmative action has affected the community’s development outcome isn’t just limited to Sachar Committee Report. The recent Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) is also indicative of this marginalisation. The Worker Participation Ratio (WPR) which measures the percentage of the employed persons in the population has been 3% lower than the national average and lowest across all major religions.

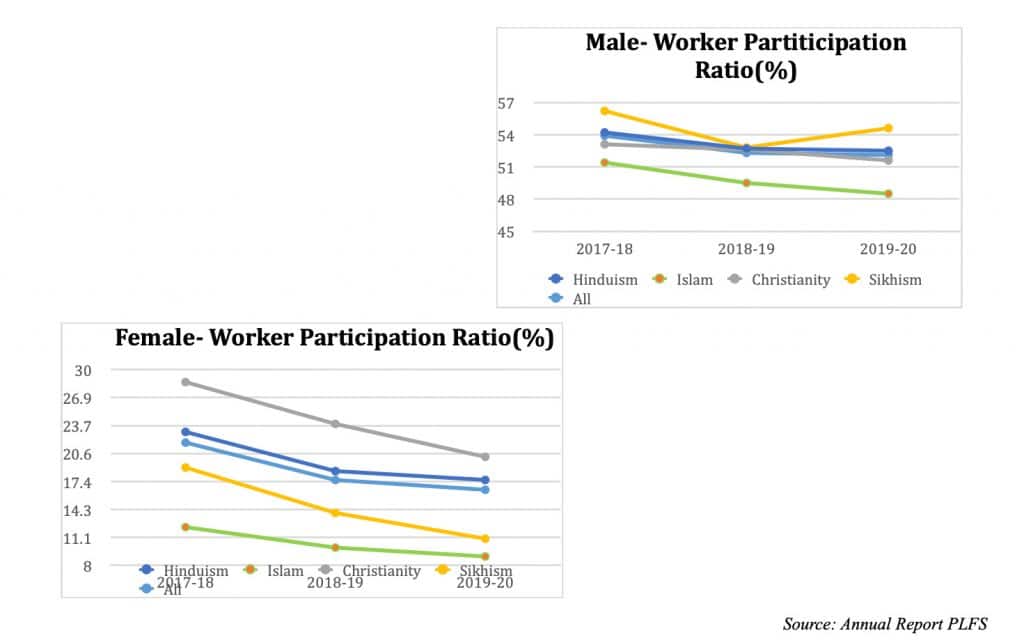

At first instance, it can be looked through the lens of gender as indeed Worker Participation Ratio for Muslim women is lowest among all social groups. This can be easily attributed to the popular imagination of Islamic conservatism with ‘purdah’ and ‘triple talaq’, however, on the contrary evidence by Deshpande et. al. (2021) suggests that veiled Muslim women have the same probability of participating in the conventional labour force as Hindu women. This shows that there might be multidimensional factors at play here for this lower worker participation ratio.

The picture becomes clearer when we disaggregate it by gender, where we find that for both male and female Muslim worker force participation is lower than the average. Multiple previous studies have shown that this lagging behind might be the culmination of broader discrimination in labour markets, lack of access to educational and health facilities.

Ghettoization also limits work opportunities significantly. Thorat and Attewell (2007) found that while controlling for other factors, upper-caste Hindus had a higher probability of getting a job offer than a Muslim or a scheduled caste candidate. According to the 2011 census, only 8.7% of all minorities taken together, work as public sector employees in contrast to their 20% proportion in the population. Basant (2012) has shown that the density of schools within 3 km of Muslim-dominated locality is much lower than the national average. In terms of educational attainment, Sen and Dreze (2013) have shown that Dalits (35%) and Adivasis (46%) have higher prospects of complete elementary education than Muslims (33%) when compared with Upper caste Hindus.

Asher et al (2018) have attributed that educational quotas, government job reservations, and other affirmative action policies that were targeted towards SCs and STs may have contributed to the upward mobility gap that has emerged between Scheduled Castes and Muslims and Bhalotra et al., (2014) found that increasing political Muslim representation improved the health and education outcomes of the community while not having any adverse impact on development outcomes of other religious communities.

Conclusion

In the broader scheme of South Asia, the Indian experience has been one of democratisation. However, democratisation is both an inclusionary as well as an exclusionary process. Inclusive because it essentially initiates a participatory political project that seeks to bring people irrespective of caste, creed, race, or community together in different strides of social life. This is also what makes it an exclusionary process as it requires a high degree of cohesion by its participants and those who differ in many ways are excluded.

The framers of the constitution were guided by their differentiation between the notion of differences and disadvantage where minorities were considered merely different from the majority whereas the state policy for preferential treatment of SCs and STs considered these groups disadvantaged from the wider society due to historical injustices accorded to them.

However, it has become imperative for the state, which has construed the principles of secularism-equal treatment of all its citizens to deny affirmative action to Muslims despite glaring evidence of Muslim disadvantage, to move from the idea of formal equality to substantive equality as state policy and accrue much-needed entitlements in order to bring Muslims on par with the other communities.

Taha Ibrahim Siddiqui is a student of Economics at Jamia Millia Islamia and a researcher at Research Institute of Compassionate Economics, working with Prof. Diane Coffey on neonatal mortality and low birth weight babies in Uttar Pradesh. Siddiqui’s research interest pertains to the political economy of development, especially questions that cater to minorities’ development outcomes in South Asia.

References

Adukia, Anjali, et al. “Residential Segregation in Urban India.” Available here (2019).

Ahmed, H. (2019). Siyasi Muslims: A story of political Islams in India. Penguin Random House India Private Limited.

Ali, M. (2010). Politics of ‘Pasmanda’Muslims: a case study of Bihar. History and Sociology of South Asia, 4(2), 129-144.

Asher, S., Novosad, P., & Rafkin, C. (2018). Intergenerational Mobility in India: Estimates from New Methods and Administrative Data. World Bank Working Paper.

Bader, Z. A. (2019). Muslims, Affirmative Action and Secularism. Economic & Political Weekly, 54(42), 53.

Bajpai, R. (2000). Constituent assembly debates and minority rights. Economic and Political Weekly, 1837-1845.

Basant, R. (2012). Education and employment among Muslims in India: An analysis of patterns and trends.

Bhalotra, S., Clots-Figueras, I., Cassan, G., & Iyer, L. (2014). Religion, politician identity and development outcomes: Evidence from India. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 104, 4-17.

Chakrabarty, B. (2008). Indian politics and society since independence: events, processes, and ideology. Routledge.

Deshpande, A., & Kabeer, N. (2021). Norms that matter: Exploring the distribution of women’s work between income generation, expenditure-saving, and unpaid domestic responsibilities in India (No. 2021/130). WIDER Working Paper.

Drèze, J., & Sen, A. (2013). An uncertain glory: India and its contradictions. Princeton University Press.

Jalal, A. (1994). The sole spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the demand for Pakistan (No. 31). Cambridge University Press.

Jodhka, S. S. (2007). Perceptions and receptions: Sachar committee and the secular left. Economic and Political Weekly, 2996-2999.

Maheshwari, S. (1991). The Mandal commission and Mandalisation: a critique. Concept Publishing Company.

Naqvi, S. A. (2020). Muslim Women as an Oppressed Minority: Facts and Projections. WOMEN’S LINK, 25.

Robinson, R. (2008). Religion, socio-economic backwardness & discrimination: the case of Indian Muslims. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 194-200.

Thorat, S., & Attewell, P. (2007). The legacy of social exclusion: A correspondence study of job discrimination in India. Economic and political weekly, 4141-4145.

Wright, T. P. (1997). A new demand for Muslim reservations in India. Asian Survey, 37(9), 852-858.