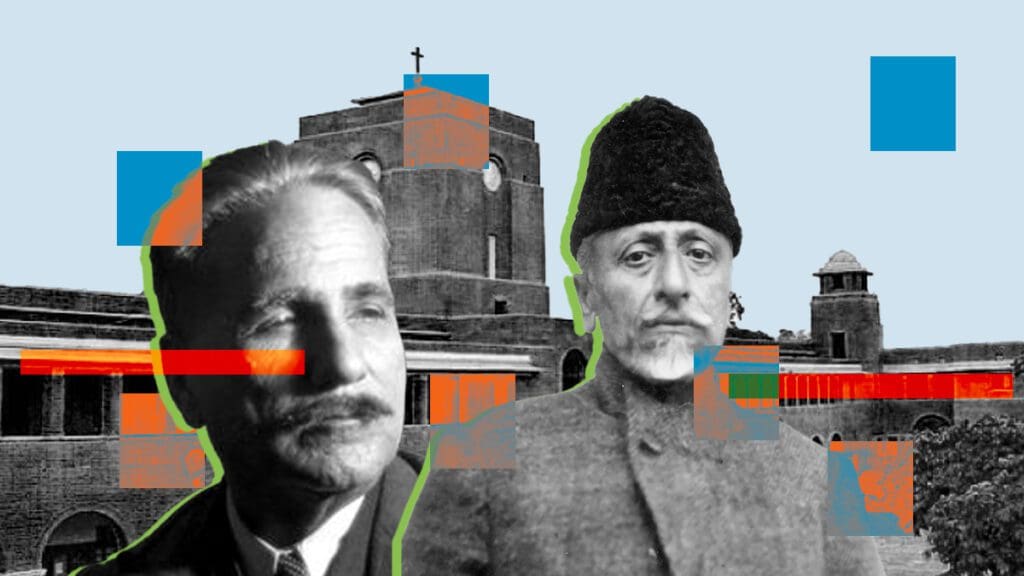

During a marathon 15-hour academic council meeting on May 27th this year, Delhi University decided to remove poet-philosopher Mohammad Iqbal from its Political Science syllabus, specifically from a chapter titled “Modern Indian Political Thought” in the B.A. program’s sixth semester. The university’s vice-chancellor, Yogesh Singh, who chaired the meeting, defended the resolution by stating that individuals who played a key role in India’s partition should not be included in the curriculum. Instead, he emphasized the importance of focusing on the teachings of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar.

The vice chancellor’s perspective on the intricate historiography of the subcontinent may exhibit a narrow focus. However, it is crucial to contextualize this decision within a broader framework that encompasses numerous measures directed towards erasing and marginalizing Muslim intellectuals and the role they’ve played in history.

The removal of Iqbal—who was educated at institutions like Cambridge and Munich—from the syllabus should not be viewed in isolation. Instead, it should be understood as a component of an ongoing project of erasure and invisibilization that was initiated by left-liberal academia and which has now been further perfected as a template—for future erasures—within the current academic climate dominated by Hindutva ideology.

If Mohammad Iqbal is regarded as the “primary architect” of the concept of partition, then Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, with his strong anti-partition rhetoric and intellectual writings opposing the very notion of partition, should have been lauded, celebrated, and given greater prominence. However, it is disconcerting to note that the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) recently removed Azad’s name from the first chapter of the class 11 political science textbook titled “Constitution – Why and How?” Previously, the paragraph in question stated, “The Constituent Assembly had eight major committees on different subjects.

Usually, Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, Sardar Patel, Maulana Azad, or Ambedkar chaired these committees.” Now, however, after eliminating Azad, it just names Nehru, Prasad, Patel, and Ambedkar. This alteration conveys a symbolic message that the Muslims of India did not have a significant role in shaping the Indian constitution. This is especially striking when considering Azad’s close association with several of his colleagues during the Quit India Movement, alongside many of whom he spent years in jail. The marginalization of Azad did not commence with the rise of Hindutva academia in contemporary Indian politics; rather, it originated with the publication of his posthumous work, India Wins Freedom, in which he blamed Nehru and Patel for the partition and marginalization of the Muslims of the subcontinent.

There is another point to consider. If the partition of the subcontinent is established as the benchmark for inclusion or exclusion within the new academic syllabus, then due recognition and celebration of the writings by Mawdudi, which vehemently oppose the Muslim League’s identity politics and the ‘haphazard partition proposal,’ should have been prioritized. Additionally, the Aligarh Muslim University should not have been compelled to withdraw Mawdudi’s works from its curriculum. Similarly, the scholarly contributions of figures from the Deoband Movement—such as Sayyid Ahmad Shaheed, Shah Ismail Shaheed, Mahmoodul Hassan, and Hussain Ahmed Madani, whose sacrifices for the freedom struggle of India deserve at least a mention in the footnotes of left-liberal academia—have been neglected.

Within the purview of left-liberal academia, Iqbal is perceived as representing a stream of Muslim intellectual thought that combines modernism with a sense of Muslim supremacy. Mawdudi, on the other hand, is categorized as a fundamentalist, while the ulemas of Deoband, including Madani, are seen as proponents of orthodoxy and ritual purity. Azad, it seems, is deemed acceptable only in the context of his post-Khilafat movement avatar. However, from the perspective of Hindutva academia, these diverse figures share a common thread: their ideological and pragmatic machinations aimed at securing the future of Muslims within the evolving landscape of colonial modernity and the rise of a Brahmanical India.

There is little doubt that a reductive understanding of South Asian Muslim intellectual history and tradition pervades mainstream academia. Muslim intellectuals are often subjected to binary categorizations, such as premodern (medieval) versus modern, regressive versus progressive, and exclusivist versus inclusivist. This tendency to confine Muslim intellectuals within rigid labels not only propagates violence against the historical context in which they lived but also reveals methodological poverty and conceptual naivety within the realm of Indian academia. Muslim intelligentsia within the subcontinent has always engaged, reconciled and tried to navigate the new terrains brought by the colonial state. They have, politely, and at times fiercely, agreed and disagreed with each other. There are overlaps and moments of departure in their work. Not having a proper semantic and semiotic understanding of their writings will only hasten their marginalization, which the brushing over of their historiography by leftist academics and the systematic erasure of their existences undertaken by rightist intellectuals has already set in motion.

Iqbal’s intellectual engagement encompasses cutting-edge discourses of his era, situated at the intersection of political theology, modernity, and spirituality. He can be aptly characterized as a critical thinker who grappled with the philosophies of luminaries such as Bergson in the realm of time and space cosmology, Hegel in terms of dialectics, Kant about rationality, Marx with regards to class structure, and Acton in the context of the nation-state. Only after traversing such intellectual terrains did Iqbal conclude the centrality of Tawheed (the concept of the oneness of God) in his philosophical framework, significantly influencing the philosophically rich “Sermon of Allahabad” and shaping the future trajectory of the subcontinent. Sweeping statements like labelling him the “architect of partition” will only serve to reinforce and vindicate his discursive legacy in various ways.

The historiography of India has become a casualty of an ongoing clash between two rival ideological blocs: the nationalist and the left-liberal historiographical projects. Amid this confrontational dynamic, Muslim historiography has suffered as collateral damage, being silenced and stripped of its richness and its agency. The history of Muslims has been appropriated, distorted, mutilated, strategically cherry-picked, and rendered invisible by both of these competing camps. While history writing and selective cherry-picking of ideas and ideologues have traditionally been the domain of the left, the Sangh-affiliated camp is now appropriating the same project, employing a pick-and-choose methodology based on their ideological convictions. Consequently, the intellectual history of Muslims remains marginalized, existing on the fringes of both camps, neither here nor there.

Both The Centre for Political Studies (CPS) at Jawaharlal Nehru University and the Department of Political Science at the University of Delhi—premier institutions that play an important role in crafting an alternative political discourse in India—sorely lack depth and insight in comprehending Muslim political and intellectual currents. Having been a student of both these spaces, I can say with firsthand experience that the faculties within these institutions display a lack of understanding regarding Islam and its critical, layered, and nuanced history within the context of colonial modernity. Beyond a paper by Professor (Retd) Valerian Rodrigues on Islam, CPS has produced nothing substantial on South Asian Islam throughout its five decades of existence, thereby precluding any meaningful debate on the topic.

Even in the construction of Hindutva historiography, Hindutva historians—such as Jai Sai Deepak, Vikram Sampath, and others attempting to sanitize the Hindutva racial project with a decolonial methodological turn—must grapple with the core philosophies of figures like Iqbal, Azad, and Mawdudi. Without a thorough study and teaching of the primary texts written by these philosophers, the history of “decolonial Hindutva” (if that means anything!) will remain an incomplete endeavour.

Academic freedom, critical thinking, and intellectual vibrancy entail engaging with a wide range of texts, including Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History by Savarkar, Bunch of Thoughts by Golwalkar, Ambedkar’s Riddles in Hinduism, Das Kapital by Marx, Prison Notebooks by Gramsci, works by Hegel and Kant, Azad’s Al Hilal and Khutbaat, Iqbal’s Development of Metaphysics in Persia and Reconstruction of Religious Thought, Madani’s Composite Nationalism and Islam, and Mawdudi’s Deen kai Chaar Bunyadi Istilahaat and Tehreek Azadi-e-Hind aur Musalman.

Only through a critical and nuanced reading and an avoidance of the pitfalls of binary constructions can the true intellectual potential and richness of these texts be explored. Unfortunately, both left-liberal and Hindutva academia are shrinking the space for reading things.

Shafa’at Wani is a research scholar. His research focuses on South Asian Muslim Intellectuals Traditions.