Welcoming, Sivakami (33) laid a mat on the platform of Ayanavaram bus depot in Chennai and introduced the thirteen families that have been living on the bus platform for four generations. The third-generation Kattu Naicker, a scheduled tribe, cautioned her kids not to play on the other side of the platform where buses run.

“When I was taken to deliver my first child, a two-year-old was hit and killed in this depot. Kids keep running and we have to remind them to stick to this side of the platform,” Sivakami told Maktoob.

Ayanavaram bus depot, seven kilometres away from the heartland of the city, is a picking point where labourers are picked early morning for the construction works around the city.

For 13 families, the depot is home for the last four generations.

Many a time, apart from unaffordable monthly house rents along with the security deposit, it is also the proximity to the place of work that keeps the poor to the pavements.

“After the midnight unloading work in markets, the labourers sleep on the pavements. There is no public transport to commute at odd hours and with the bare subsistence wage they get, they also can’t afford to commute,” R. Geetha, secretary of Nirman Mazdoor Panchayat Sangam, explains.

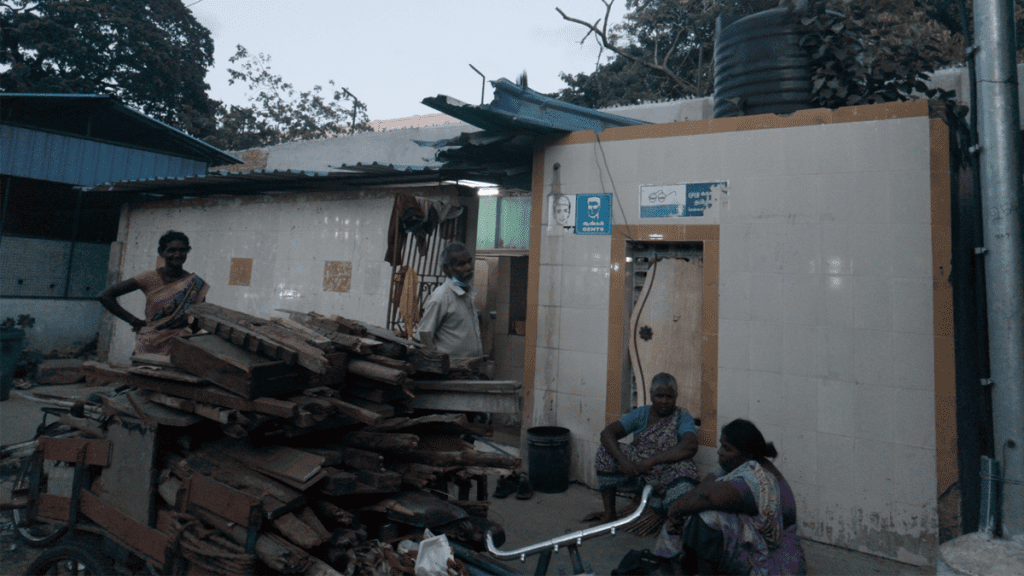

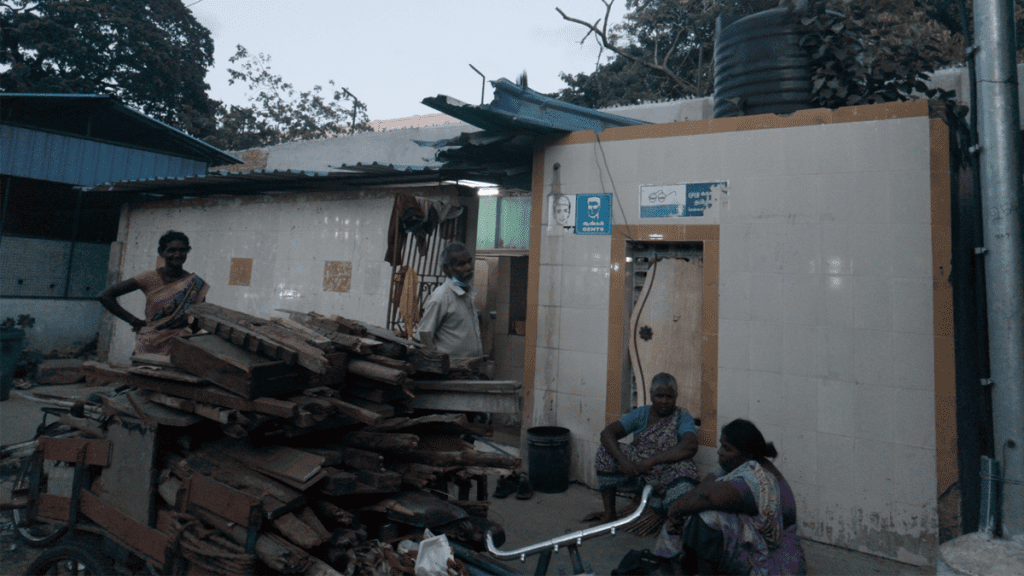

Apart from the possible hit and run vehicles, Sivakami is also constantly under threat of eviction. And with every eviction drive, what follows are wageless days and settling works; arranging water for cooking and ensuring safety and access to public toilets.

Since the dwellings are decided by the proximity to the place of work, eviction of pavement dwellers becomes the elimination of their very livelihood and denial of the right to life, under article 21, observed Justice Y.V Chandrachud in the Olga Tellis vs Bombay Municipal Corporation case in the Supreme Court in 1985.

However, eviction threats hang upon them, where their belongings will be thrown out and taken to shelter homes or simply shooed away by the corporation officials.

“But families can’t live in shelters, as government shelters are gender-segregated and they would not want to get separated,” pointed out R.Geetha.

Looming uncertainity

In times of online education, eviction threats prevent parents from going to work, since they are worried about leaving their kids alone.

None of the adults in Ayanavaram depot, have been to school, and are largely illiterate. Today’s children are going to school and the eldest of them is a ninth standard student.

Nevertheless, two years of online education has only pushed back further the long-oppressed community.

“Born here, I grew up seeing the wastelands around Ayanavaram mushrooming into a city,” says Vasantha, a 55-year-old widow and the eldest of the thirteen families.

According to Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board estimates, there are 1.1 lakh homeless households, and the 2001 census says, the slum population in the city was over 10.79 lakh, which is 26 percent of the city’s total population.

Chennai slums have their fourth or fifth generation children playing on the outskirts of the city; under the bridges, or beside the river endings or railway stations.

Calling them encroachers in policies is wrong in itself. They are squatters. And the very beginning of squatter settlements has a history weaved with work.

“From the time of the British and later times, when shelter demands of factory and markets workers were neglected, they decided to squat or live in places near to their workplace,” R. Geetha points out.

Shrinking livelihood

Knotting flowers in a rhythm, Maheshwari (28) said, “We tie flowers and each kottai (bundle) brings 50 rupees. If we can sell flowers on our own, we would fetch more, but then we don’t get to put out our own shop. We get hassled away by other sellers.”

When women bring 300 rupees, men get 700 rupees per day for construction works.

“Just like today, there are also jobless days where we don’t get work,” Kumar said. “We take up any manual work, including clearing clogged drainages and other construction work including loading and unloading,” added Kumar.

“On festive days like Ayudha puja and Pongal (harvest festival), we are taken to the police stations to broom and clean. They buy us Porotta and sent us off with a mere 50 rupees. When we demand more, they thrash us,” says Kumar.

“And when they fail to get the accused they pick us and file charges on us. Just that each time our names and addresses will be changed”, Kumar added.

Constitutionally, these squatter settlers are supposed to be rehabilitated into proper houses. Either they must be given the patta (legal right) to the land in which they have lived for generations and laboured for the development of the city around them, or be given houses proximal to their workplace.

Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board, recently renamed as Tamilnadu Urban Habitat Development Centre has time and again brought policies and worked in collaboration with the centre’s housing policies like Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana and constructed huge buildings with World Bank funds.

“But then houses are allocated only after a minimum payment of 1 lakh rupees, which microfinance companies are eager to provide as loans. And that becomes an added debt trap into their lives,” says Vanessa Peter, founder of Information and Resource Centre for Deprived Urban Communities (IRDUC)

Apart from irregular workdays and eviction threats, the daily get going of life itself is a draining affair.

“We pay public toilets 30 Rs for bathing and 50 Rs for washing. And these days phone charging expense to the nearby shops has also been added to our daily expenses,” says Sivagami.

In addition to the daily financial anxieties, with the sun setting the insecurities over living in the streets spreads.

“Getting to toilets with young girls is a difficult task. Drunkards and perverts are keen to molest our girls,” Sivakami says. “Though in the daytime we are seen with disgust, ironically by evening things turn over”.

It was only after six years of struggle with paper works and waiting at the doors of officials, could all the thirteen families get a ration card.

“Voter ID came easy, but getting ration card was a tiring battle. We had to somehow rent a house for the sake of registering a residential address for all the families,” shared Kumar.

Without a birth certificate or parents’ educational certificate, the Kattu Naiker families of Ayanavaram bus depot are struggling to get a caste certificate.

After appealing to the Chief Minister for allotting houses, they received a letter asking them to procure houses paying five lakh and eighty thousand to the slum board.

“There are enough unused lands in the city. We only have to map them and allocate them,” Geeta added.