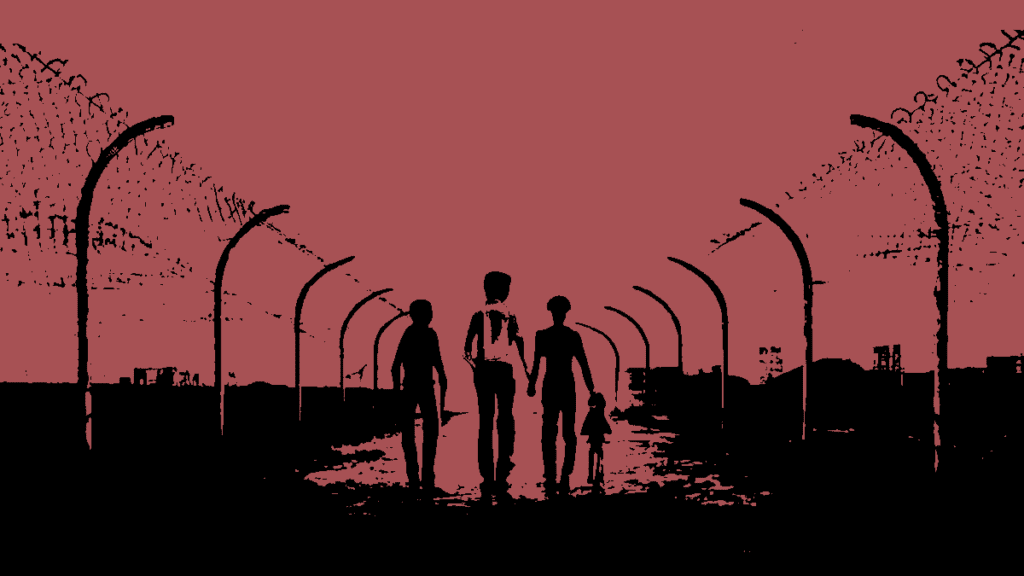

On July 01, 2022, Nur Hafez and his family crossed Indo-Bangladesh once again to return to Cox’s Bazar, where nearly a million Rohingyas like him are living in the largest and most crowded refugee camp in the world.

The 41-year-old had left the camp in 2017 with his wife and two children, to enter India illegally and settle in the national capital, New Delhi. He retraced the risky illegal journey as he couldn’t bear being imprisoned again in life.

“I don’t want to live in fear,” Hafez said.

Several Rohingya refugees who entered India due to ethnic violence Rakhine state of Myanmar, share the agony of being unwelcomed in India. In 2017, as a brutal military crackdown in Rakhine forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee, the Minister of State for Home Affairs (MHA) in India issued a directive to state governments asking them to identify all “illegal immigrants” within their respective borders, for deportation.

“Infiltration from Rakhine State of Myanmar into Indian Territory especially in the recent years besides being a burden on the limited resources of the country also aggravates the security challenges posed to the country,” read the directive.

Despite this MHA estimates about 40,000 Rohingyas live in India with approximately 18,000 registered with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

But even people with refugee cards are being detained in India.

Hafez said “no Rohingya” wants to stay in India due to the state’s apathy but due to crackdown during any movement have kept them stranded in camps.

“We were called weekly for a head count by the local police. They would threaten us about detention. I couldn’t take it anymore. My children were called infiltrators by other students in school,” Hafez said.

Hafez was nine when his family shifted to Bangladesh in 1991. In 2003, he was arrested while visiting his relatives in Myanmar and jailed for five years. Before he was released and sent to Bangladesh in 2008, his family members had relocated to Canada.

“Rohingyas were getting harassed or detained every day. I didn’t want my family to go through it. It was a life with no dignity,” he explained.

While he finds it hard to find a job in Cox’s Bazar camp, he says the security of living with the community is better.

“Several people have returned. Many more are waiting for an opportunity,” Hafez added.

Human Rights Watch has urged India against deporting Rohingya Muslims citing “the serious risk they face of persecution”.

Illegal to live, illegal to leave

An activist associated with the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative, a refugee advocacy group based in New Delhi, who wants to remain anonymous fearing reprisals, said camps have turned into prisons.

Growing surveillance and threats of detention forced him and some of his colleagues to leave India for another South Asian country.

“I was asked to become an informant by intelligence officers. FRRO (Foreigners Regional Registration Officers) keeps calling us every week and blatantly threaten us,” he claimed.

FRRO warned him not to do advocacy and not travel outside New Delhi. He claims an attempt to go to another state through the airport landed him in detention for 10 hours before lawyers came for his rescue.

“People got picked up from railway stations while trying to go back to Bangladesh in Assam. Even leaving is not allowed in India.”

The activists and Hafez confirm that they used the help of smugglers to make these travels and the risk of being exploited is high.

“Women are more vulnerable to trafficking in these journeys,” the activist added.

Several applications for exit permits by Rohingya Muslims to travel to relocate were rejected by Indian authorities despite having documents.

In 2022, the Indian government said that it cannot grant exit to illegal migrants to a third country.

In a submission to the Delhi High Court, the government said that supporting or facilitating the resettlement of “illegal migrants” in third countries would be “detrimental to the international relations of the Indian government.”

However, due to pressure from the group ahead of the G20 Summit in 2023, several permits were given to Rohingya Muslims with resettlement visas.

Hamid Hussain, who married a Canadian-Rohingya woman, was sent back five times before his permit was approved by FRRO.

“They finally asked me to pay a penalty for the illegal stay before giving me the permission,” Hussain said.

State apathy

A fresh petition in the Supreme Court Of India is seeking “to release Rohingya refugees who have been illegally and arbitrarily detained in jails and detention centres across the country, to protect their right to life and equality before law under Articles 21 and 14 of the Constitution of India, guaranteed to all persons residing in India, citizens or otherwise.”

Nearly 700 Rohingya refugees are facing indefinite detention in India, while the Hindu nationalist regime led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi is pushing for their deportation.

But Fazal Abdali, a lawyer who worked on refugee rights in India, says Rohingyas have been repeatedly let down by the Indian state and courts.

In 2018, the Supreme Court of India rejected a plea urging authorities to stop deporting Rohingyas. And again in 2021, the apex court judgment paved the way for more deportation.

Working for over a decade with Rohingyas, Abdali claims “state and society” are forcing another “exodus” of Rohingya from India.

“They live in fear. They are targeted for every bad thing happening in the cities they take refuge in. It led them to scatter into many Indian cities that added to the vulnerability,” Abdali said.

“In opposition to the phrase Atithi devo bhava and Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (which is also on the BJP manifesto) the attitude towards the Rohingya, who are fleeing persecution is one of hatred and contempt. India has to change that and abide by its international obligations,” Aakar Patel, Chair of Amnesty International India, said.

“Seeking asylum is not a crime,” he added.

“People are coming back to Bangladesh. We ask our relatives to come back as we can’t help them in India,” a Rohingya activist based in Cox’s Bazar refugee camp, who requested anonymity, said.

He said while the affluent can get help from smugglers and agents to travel, others have to take more risks.

Campaigners and journalists from Bangladesh confirmed that Rohingyas are returning from India.