In March 2020, a pro-right-wing news website, Indus Scrolls, published an article attacking journalist Siddique Kappan for his links to Jamia Millia Islamia and his relation with Islamic groups. Although he thought it was silly, his publication, Azhimukham, urged him to file a defamation.

Seven months later, in an interrogation room in Uttar Pradesh’s Mathura, Kappan was confronted with the same accusations. Statements from the editor of the Hindutva outlet, G Sreedathan, land Kappan in jail for the next 28 weeks under India’s terror law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

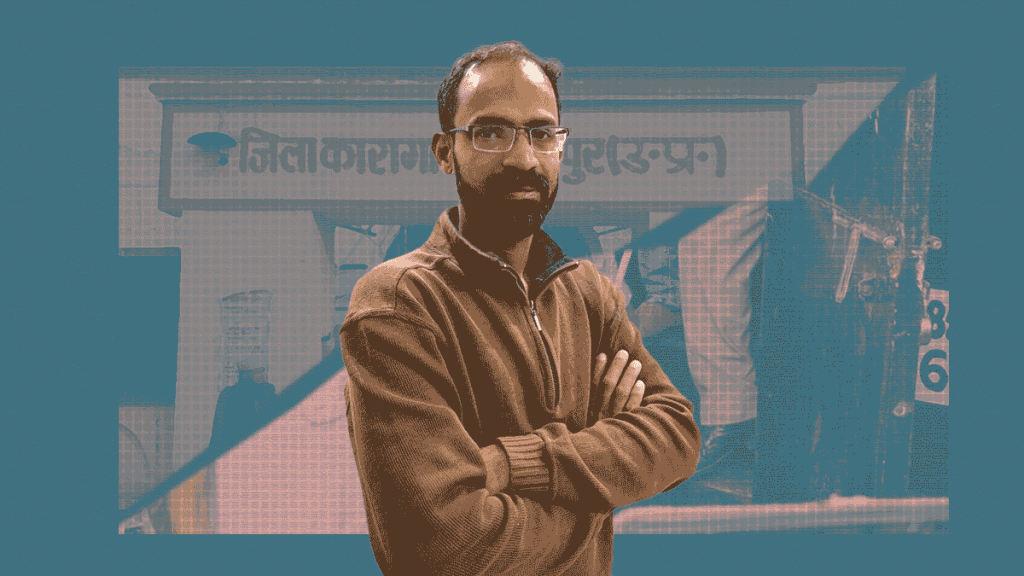

“It was two years of torture,” Kappan, who is released on bail, told Maktoob. “Not just me, my family went through the worst.”

According to critics, Kappan’s ordeal during his incarceration reflected India’s deteriorating press freedom. While granting him bail in September 2022, the then Chief Justice of India, UU Lalit stated, “Every person has the right to free expression. He is trying to show that victim needs justice and raise a common voice. Is that a crime in eyes of law?”

“I was only doing my job,” the Malayalam journalist reinforced.

On 5 October 2020, Kappan was arrested on his journey to Hathras to report about the gangrape of a teenage Dalit girl by upper caste Hindu men who eventually died in hospital. His co-passengers — Atikur Rahman and Masud Khan, leaders of now banned Muslim students outfit, Campus Front of India and the cab driver, Mohammad Alam, were also arrested for “anti-India conspiracy”.

Hours leading up to their journey, 19 cases were filed across Uttar Pradesh to hatch the “deep conspiracy” behind the outrage against the Hathras Dalit rape case. The FIRs were filed a day after UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath claimed that the Hathras incident was being exploited by those who were upset at his government’s progress.

Police stopped opposition leaders including Rahul Gandhi and journalists from reaching Hathras. Reports suggest the family of the Dalit girl was threatened by the administration and even kept under house arrest.

“I wanted to go like any other reporter. It is not a terror act”.

Released on 2 February, Kappan will stay in Delhi for six weeks as per UAPA bail condition, before leaving for his home state Kerala.

“I will have to attend court a few times a month. So leaving Delhi may not be a choice. But now I want to go home for some time and then see what happens next,” Kappan said.

“I became the perfect scapegoat”

“Police had a photo and were checking every car at the checkpost in Mathura. Later I learnt they were looking for Atikur Rahman,” Kappan revealed. “That doesn’t mean he [Rahman] had a bad intention but he must have been someone on their watchlist.”

The cops at the checkpost summoned them to the station for Bathcheeth (chit chat). “We were told to stay back for some questions. While the cab driver intended to drop us off and leave, he was asked his name and then roped in with us,” Kappan recalls.

The detention was casual with police providing tea and snacks to the group until a local intelligence officer arrived in the evening. When he found out Kappan was a journalist from Kerala, he misbehaved.

“They slapped me and began asking absurd questions. They were sure that I went to Pakistan but they wanted to know how many times. The abuses were very disturbing,” Kappan described.

Kappan claims that he was asked about which leftist lawmaker from Kerala sent him and who funded him. He was alleged as the mastermind of a conspiracy that remains unclear, even in the chargesheet, according to lawyers.

“I had 4500 rupees with me to pay for the taxi. They made it look like funding for rioting,” he said.

Initially, the group was booked under 151 IPC— Knowingly joining or continuing in an assembly of five or more persons after it has been commanded to disperse. But soon, Uttar Pradesh Special Task Force, Arga Anti Terrorist Squad and Lucknow Anti Terrorist Squad were involved. Kappan also claims that they were forced to sign blank papers under pressure.

“We were tied with a long rope as if we were cattle and brought to the court. Local reporters were calling us “terrorists” and there was a huge deployment of armed forces. I realised something bad is going to happen.”

Kappan recalls that a policeman leaned to him and told him that a case have been filed in Supreme Court and informed him about his lawyer.

“If was the first information from the outside. I clearly remember him,” Kappan said. At the local court, they were informed that UAPA is added to the FIR against them.

28 weeks in jail

For months, Kappan had no idea about what was happening back home. It took weeks for him to establish contact with his family as physical meetings were restricted due to the pandemic.

“The jail had three times more inmates than its capacity. We were seventy people in one barrack,” Kappan remembers. “Because my case was heard in the Supreme Court, the jailer once told me to complain to the court about the situation. Even they were worried.”

But the worst moment came when Kappan was infected with COVID-19 amidst Ramadan. “One day when I woke up for Sehri (morning food), I collapsed. I was taken to the jail dispensary and later shifted to KM Medical College”.

For the next five days, Kappan was handcuffed to his bed and not allowed to go to the bathroom. He was forced to urinate in a bottle. When it started to spill, someone came into his room.

“I don’t know if he was a staffer. I gave him 500 rupees a fellow jail inmate gave me and asked him to buy me a water bottle and juice. I was looking for good bottles. I was so desperate.”

Kappan said it was not the police but the hospital manager who was vindictive and made sure he suffered. “He would scream at me when he saw me,” he recalls.

Kappan was later shifted to Dlehi AIIMS for better care. But the police brought him back even before he was cured. It took a quite long time for him to regain his health.

In early 2022, Kappan was shifted to Lucknow jail.

Wife battled, Children suffered

“It was a tough time for my children. I couldn’t be there for them through it. Their education was hit. Even when I meet them in court, I could see the despair on their face,” Kappan, father of three, lamented.

“My wife and my 17-year-old son had to travel to unfamiliar places for me. These are otherwise considered dangerous trips. Even my bail plea in Supreme Court was under Raihanath’s name after jail authorities held on to my papers for a long. They were adamant about not letting me walk free”.

Kappan’s sureties were allegedly threatened by police officers and harassed under the pretext of background inquiry. It took three months for the verification of sureties in the UAPA case.

“Everyone was anxious until I walked out. Police wanted to keep me inside to silence us. Since 2014, there is a steep fall in values in this country. Others who are booked in this case are also innocent because the case itself is bogus,” he added.