“I protected myself but I knew there are girls out there who are facing the same problem in lockdown. I knew we needed to unite and help each other”, says 17-yr-old Priyanka Bairwa whose parents wanted to marry her off due to economic distress after lockdown 2020. She was sixteen at the time and managed to convince her family against her marriage.

Priyanka resides in Ramthara village in Karauli district of Rajasthan. She realized speaking for herself wasn’t enough and lead the campaign ‘Rajasthan Rising’ against child marriage in her village. Started with 10 fearless girls, the campaign has spread to more than 50 villages connecting 1240 girls in Karauli district of Rajasthan.

Priyanka’s mother Urmila works as a house help and earns Rs.8000-Rs.10,000 per month. Her income declined sharply due to lockdown. Priyanka also started working with her mother to support the family. Urmila’s income does not suffice her husband’s medical expenses and the education of her four children. Her father has been severely ill for the past few years and does not earn.

Out of the population of 1,534, Priyanka’s village Ramthara has 530 SCs and 357 STs as per census 2011. The impact of COVID-19 on family incomes has impacted the education and agency of girls as the economic stress frequently drives families to marry their daughters off early. The ongoing pandemic has undermined the progress made towards achieving gender rights and educational parity for girls.

“They didn’t stop talking about my marriage. In protest, I stopped working as a house help with my mother. When they saw the income get restricted they agreed to my demand,” Priyanka told Maktoob about her own non-cooperation movement at home. The girl says she was helped by Alwar Mewat Institute of Education and Development (AMIED), an NGO where her mother is a domestic worker. AMIED volunteers convinced Urmila against child marriage.

The central government’s national Childline helpline 1098 had responded to 460,000 calls in 21 days, or nearly 22,000 calls a day, with a majority of them received during the countrywide lockdown from March 20, 2020, to April 10, 2020. A year later, the second wave of Covid-19 in India has meant that its 424 million children (aged 0 to 17 years) continue to be vulnerable, according to a recent report by India Spend.

Becoming a force against child marriage

“I started looking for other girls like me. I managed to connect with ten girls. We found that those girls also faced the same problems and had stopped a lot of child marriages,” says Priyanka as she gives details about the formation of the Rajasthan Rising campaign.

The girls laid a proper plan to expand the team and amplify their cause. They knew raising voices in their house or village alone would not suffice the menace.

“Now that there were ten girls, each girl picked five villages. Thus, we could reach 50 villages. They visited their respective five villages and gathered girls. We used to sit in a circle and talk about effects of child marriage, gender discrimination, the importance of girl child education”, continues Priyanka.

Then they picked two girls in each of those fifty villages as the village leaders. These 100 girls held a meeting and interacted and trained each other regarding how to communicate with the villagers. Every girl of these 100 connected with 10-15girls each and now they are a team of 1240 girls.

Stories of distress and valiance: Rajasthan Rising

“When the groom’s side came for a meeting, I categorically told them I don’t want to get married. They thought I was being arrogant”, says 17-yr-old Neelam. Lockdown induced job loss compelled Neelam’s father to arrange a marriage for her.

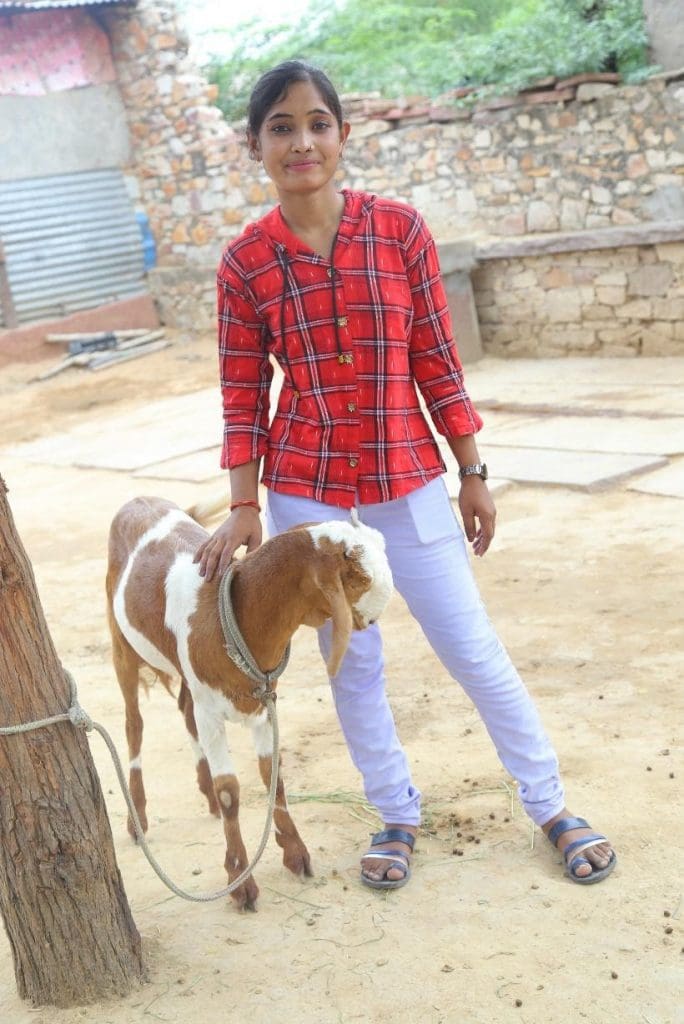

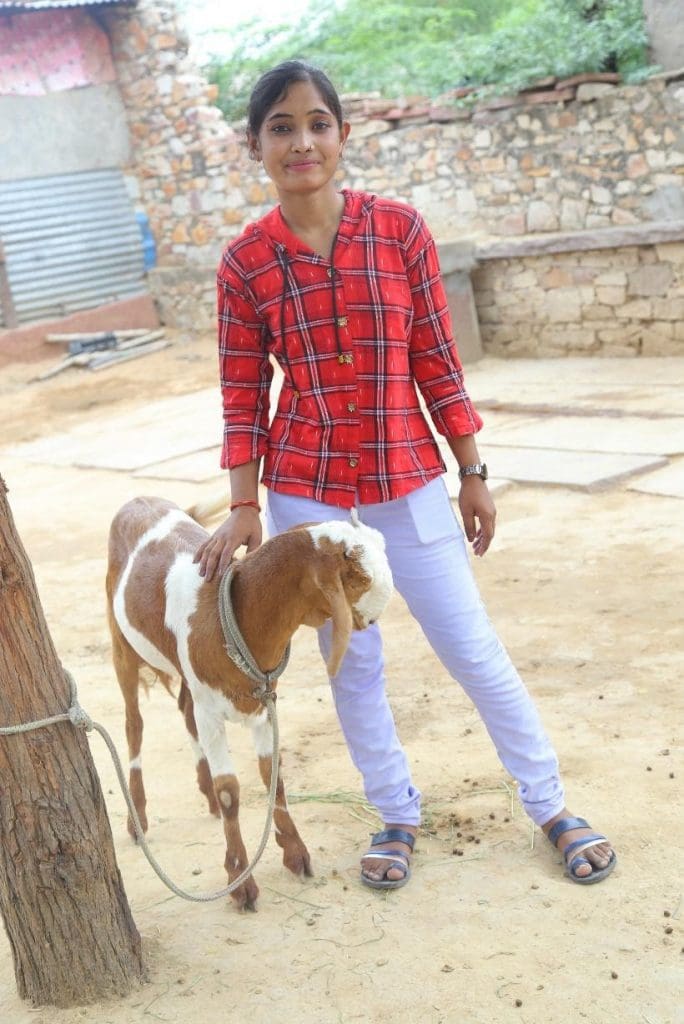

Neelam’s father worked as a tailor and earned Rs.5000-Rs.8000 in a month. Covid-19 induced lockdown and decline in orders hampered his travel to Jaipur for work. The family of five is now dependent on their four goats for income.

When the groom’s family visited Neelam’s house she was already a part of Rajasthan Rising, the campaign lead by girls against child marriage. Neelam says “ It was only after joining the campaign that I could gather the courage as then I realised the drawbacks of early marriage. Earlier I thought it was ok. I never really gave it a thought.”

The risks associated with child marriage do not end with girls who are married before 18 but it also leads to an intergenerational cycle of poverty. It puts girls at risk of being denied access to education, which impacts their autonomy and their access to health care. Child marriages perpetuate gender discrimination, which in turn lead to malnutrition and reproductive health issues. The ongoing pandemic has undermined the progress made towards achieving gender rights and educational parity for girls.

“When my younger sister Khushi turns seventeen they won’t pressurise her to get married. They know we would refuse even if the groom is right in front of us”, says Neelam with pride.

The girls regularly host rallies in the village in groups and go house to house for spreading awareness against child marriage. They sit together, make posters and paint walls with beautiful messages to prepare for their rallies.

“We want our campaign to reach corners of Rajasthan and spread throughout the state”, says 17 yr-old Saira Bano who resides in Kurgaon village of Karauli district. Saira joined the ‘Rajasthan Rising’ campaign against child marriage in October 2020.

Saira’s father had no job and the family had no source of income after lockdown. Repeated lockdowns and shutdown of schools led her parents to arrange a marriage for Saira. The guest restriction due to Covid-19 would reduce the expenses of the ceremony thus, Saira’s parents considered it to be the ideal time to plan her marriage. Saira refused and convinced her parents with the help of other volunteers of Rajasthan Rising.

In Saira’s village Kurgaon 43.85 % of the population is involved in Marginal activity providing livelihood for less than 6 months. The average literacy rate in the village is 69.06% i.e. 82% for males and 54.78% for females as per census 2011.

“Villagers used to tell us our rallies won’t make a difference but we see the change now. People now don’t see us in a bad light and realise that we might be successful” says Saira Bano when asked about the response of the villagers.

When asked about the marriage of her 13-yr-old sister Khushi she said, “Yes they might think of getting Khushi and I married together to save money. This is out of sheer poverty. They don’t agree with child marriage but they are helpless. I wouldn’t want that. Just like I stopped my child marriage I want to stop hers too.”

“Our sarpanch Mr. Bishnu Verba also supports us. We hold meetings with him twice a month. He even talked to the MLA Mr. Ramesh Chandra Meena for us. He agrees with our idea and is helping our voices reach the decision makers. He even comes to rallies with us”, says Saira Bano commenting on how local governance sees the girls’ initiative.

A Fragile road to ambitions

“I sometimes carry a book when I go to graze the goats. In case, I get time on the way I would be able to read”, says Neelam as she spends her day in household chores and in taking care of her younger siblings.

Neelam wants to become a teacher for which she has to enroll herself for a B.Ed degree . The nearest college to her home is 20km away. There are no proper means of transportation in the village and Neelam has not yet planned how to manage travel for further studies.

Neelam’s village Narauli has a literacy rate of 51.28 % which is around 30% lower than the national literacy rate of 74.04%. In Narauli the average literacy rate for males is 65.44% as compared to a mere 34.31% in females as per Census 2011.

There are a lot of girls who are not educated beyond 8th standard in the village as there are no schools for higher education of girls. Unlike their sons, parents don’t send their daughters outside the village for studies. This is also a reason why girls are forced into child marriage.

“Villagers often make slurs, mostly men. We try to explain them. When we talk about our rights, they think we are spoiled”, complains Neelam acknowledging the patriarchy in her village.

“I want to be a social reformist and fight for womens’ rights”, says Priyanka, motivated by leading the change in her district. The girl even started working as a volunteer with AMIED, the organisation that helps her convince her parents against child marriage. Priyanka’s parents did not support that. They believed fieldwork and volunteering will spoil her, fearing her socialisation might lead to a love affair.

Priyanka says, “I used to feel good working there but my parents wanted me to engage only in womanly chores as a house help. They believed field work and volunteering will spoil me and I should not engage myself in any work related to studies.”

Despite the challenges the girls continue to strive for their cause. Their persistence has saved thousands against child marriage as their movement echoes in remotest corners. The girls’ aim for taking their voices to the lawmakers does not seem far away.

“Balika shiksha ka adhikar mangte; bheekh nahi adhikar mangte. We ask for the right of girl child education; we don’t beg for it, we demand our right”, says 17-yr-old Saira Bano.