On 10 May 1933, a chilling act of barbarism took place in the city of Berlin. Students from a local university, all members of right-wing student organizations, transported books from their university library and other collections to a new location and proceeded to toss thousands of titles into the flames of an ignited bonfire. The egregious act lasted several hours. German newspapers reported in triumph that Germany was beginning to purge itself of the alien and decadent corrupters of the German spirit. In the years that followed, art and literature were seized, stolen, burnt, sold, repurposed, and forever removed from public-eye as the Third Reich dictated who could be an artist and what artists could and could not create. Journalists at the time recalled the prediction of the poet Heinrich Heine, who had said a century earlier: “Where one burns books, one will soon burn people.”

Art and social movements have long held a symbiotic relationship. Art as confession, the role of the artist to reveal, to disturb the status quo and for art to be the hammer from which society is shaped rather than a mirror that reflects it, long assume dual responsibilities of the artist – of artistic practice and awareness of the context in which this practice occurs.

James Baldwins’ plethora of writing, all nuanced and dimensional, written with conviction, articulates that because of the history of American racism, Black artists possess an exceptional capacity to make art as praxis. Meaning to create and disseminate art as a deliberate and conscious act to question power structures and promote justice. Baldwin was compelled – out of circumstance and the continued dehumanization of his people that he must be an artist. He wrote, “It is not your fault, it is not my fault, that I write. And I never would come before you in the position of a complainant for doing something that I must do… The poets (by which I mean all artists) are finally the only people who know the truth about us. Soldiers don’t. Statesmen don’t. Priests don’t. Union leaders don’t. Only poets.”

Alice Neel illustrated women as consciously aware of the objectification by men and the demoralizing effects of the male gaze. Neel yielded art as a counter-narrative. Her work challenged and contradicted the traditional and objectified nude depictions of women by her male predecessors. She conveyed a depth of emotion, dignity and humanity in what was considered ‘taboo subjects’ at the time – the inclusion of pregnant women and marginalized figures which led to her recognition as an artist of the female gaze.

Known as the largest community arts project in history, The Quilt, conceived by Cleve Jones in 1987, offered a way for friends and lovers to commemorate those who were abandoned by family and the state at the time of the HIV and AIDS epidemic. Jones enlisted fourty of his friends who painted the names of deceased loved ones on scraps of fabric and began to sew these into quilts. Today, the number of panels has grown to over 49,000, over 14 million people have visited and participated in the project and the Quilt weighs an estimated 54 tons. Art as a memorial for an incalculable loss.

These moments in history reflect the role of art and literature in reclaiming voice as a form of resistance and as a mobilizer for collective action. There is also a silent work that art does, in each of us. It invites contemplation and individual interpretation. A silent critique that can foster critical thinking to reconsider an assumption. It can foster in us a cultural identity thought to be lost. It can make us feel seen. It can invite peace. It can ignite maybe the most dangerous thing – a belief in ourselves and in our collective capacity. So dangerous that over periods in history, art has been burnt, seized, controlled, and erased in attempts to erase people.

On August 4, 2019, the internet, landlines, cell phones and television were cut-off in Indian-administered Kashmir, placing its 7 million residents in a total communication black-out. On August 5, 2019, Kashmiris woke up to the erasure of their constitutional status, their flag and their identity. This caused a paradigm shift where the fight moved from being a protest against the state to one against erasure, says Kashmiri-writer and anthropologist, Onaiza Drabu. Kashmiris for months lived in collective internment with no idea of what was happening in the neighboring camp.

5 August 2023 marks the the fourth anniversary of the abrogation of Article 370, the law in the Indian constitution that granted Kashmir semi-autonomy. I spoke to three Kashmiri artists who shared their reflections on their journey in their artistic practice, the impact they hope to achieve and how their work and themselves may have evolved over the last four years.

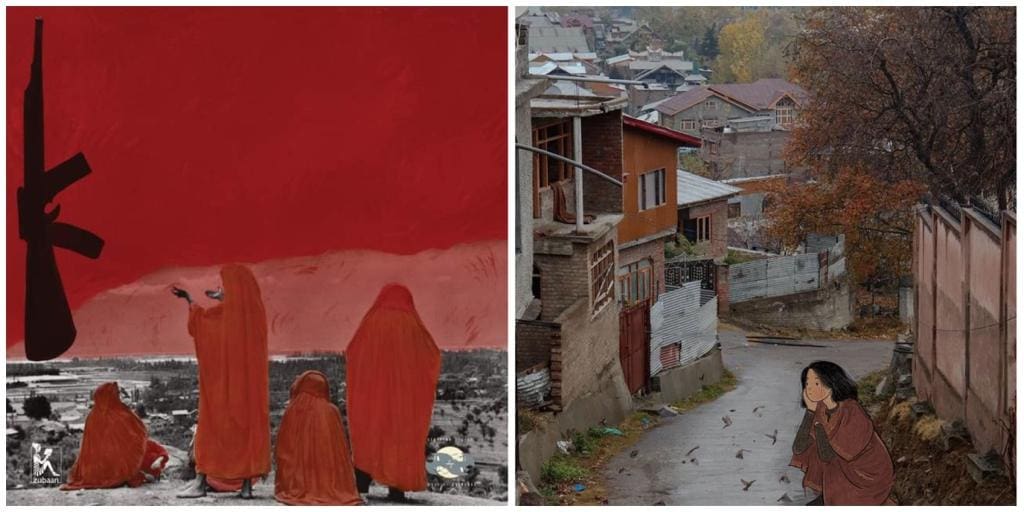

Ghazal Qadri is a Kashmiri visual artist based in Maryland. Ghazal was in the United States with her brother when Article 370 was abrogated. Her parents remained in Kashmir. Ghazal’s artistic expression is inextricably linked with portraying real-life situations in Kashmir, sometimes with a speckle of playfulness. As life came to a complete standstill in Kashmir, Ghazal’s days stretched into weeks into months before she was able to contact her loved ones. Her artistic practice became grounded in giving voice to herself, her pent-up feelings of witnessing what occurred pre-and-post abrogation. “Artists are agents of a message, for some, this message is being an agent of cultural change”, she says. For Ghazal, to inform, to persuade, to dissuade are all acts she embodies as an artist. “Art has more power than people are willing to admit.”

Inference and subliminal messages are tactics Ghazal draws upon in canvassing her art. It is not always safe for artists to steer their art in the world of political activism and then be protected from retaliation. For Ghazal, depicting and describing a feeling, a reaction or a response inspires an internal work in each of us – to imagine freedom for Kashmiri people. “Art has great potential to support movements towards liberation by creating images of a better and freer future,” Ghazal notes.

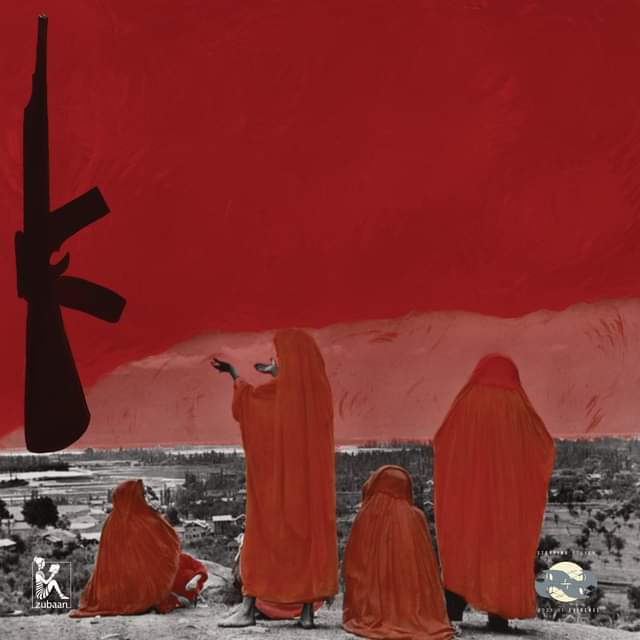

Barooja Bazuz is a visual artist from Kashmir. Barooja was in Kashmir when Article 370 was abrogated and their work has largely been impacted by being confined to their home for months during this period. While Kashmiris have been subjected to a lifetime of lockdowns in various forms since independence from the British, the silence that ensued after August 5, 2019, was a pivotal moment for Barooja as an artist. Their artistic practice was driven by an intractable drive to hold onto identity. For Barooja, they are driven by the desire to hold onto Kashmiri culture and the Kashmiri language. Barooja expands, “to document truth”. A cultural truth, of Kashmiri scenery, culture, language and its people. To evoke pride, an acceptance without shame of being Kashmiri. When the state is on a path to forcibly assimilate, some Kashmiris are losing their language, culture and identity to avoid being targeted, Barooja explained. “After the annexation of Article 370, I feel more than ever to contribute to the originality of our culture. I feel a responsibility so that it is not lost and to show the world what Kashmir really is and not what the state is changing it into,” Barooja says.

Onaiza Drabu is a Kashmiri anthropologist and author of The Legend Of Himal And Nagrai: Greatest Kashmiri Folk Tales. Onaiza also runs Daak, a community that shares stories, artworks and ideas from women and men who have shaped the Indian subcontinent’s cultural heritage.

Onaiza was in Kenya when Article 370 was abrogated. When news broke, Onaiza rushed into the toilet at her workplace and cried. She wept in anger and fear and felt it was a telling moment of the fate of her people. When asked by a colleague why she looked visibly upset, Onaiza attempted to explain the magnitude of what had just occurred. Her colleague looked at her blankly and said, “You’re crying about a policy change?”. Trivialising a moment of true personal loss. After August 5th, Onaiza moved back home to Kashmir.

Kashmir was handed down to Onaiza through stories – from four sets of grandparents which shaped her view of the world and of Kashmir. Her artistic expression – primarily her writing, is very much an exercise in a form of nostalgia – an almost magnetic recollection of memories that are often not her own but others. This is not uncommon for Kashmiris who have been displaced or for those who have lost elders and the family histories that came with them.

Onaiza’s writing is an act of self-preservation, a way to keep memory in a world that is designed for erasure. “For me it is not possible to recreate the past, but it is very much possible to use fragments, shards even, of a shattered past to understand the present and begin to imagine the future,” she says. Her work also serves a functional purpose – to preserve memory of those who are losing it. “Many women around in Kashmir – elderly women – suffer from various diseases of forgetting; dementia, Alzheimer’s and with them goes a world and a way of life. My urge is to keep their stories, to keep a way of life in a rapidly changing world,” she says. Some write because they want to remember.

In discussing how Article 370 impacted her work, Onaizaexplains, “After August 5th, I felt like it was such a pointless exercise to even talk to people about Kashmir or to engage in conversations. It was a moment where I realized people just don’t get it. I don’t engage anymore with people from the subcontinent to be honest.” Speaking about Kashmir, even in private circles, has been wrought with consequent denials, awkward cartwheels and mental acrobatics that I no longer have the sustenance for.

Our hyper-connected world with a 24-hour news cycle lends itself to constant expression, rebuttal, and protest online, this can deceive us into thinking that each voice is truly heard and respected. The ability to ‘rage-post’ – in the case of Kashmiris who so frequently are subjected to internet shutdowns – even this is a privilege. How effective online activism is, what it does to the psyche of marginalized groups whose voices are systemically silenced all become secondary to the basic human right of access to the internet.

Onaiza reminds us that protest is not just immediate, physical, visceral and loud but that it can be slow, abstract, diffused and silent. Archiving memory, tradition and tales provide an alternative to reacting to the constant barrage of information because the very act of this is archiving a past that is sought to be erased.

Art and social movements share a rich and long history. Art possesses a unique potency in its various realms – theater, visual art and verse – to convey a message. Through its inherent coding, it silently establishes a profound connection and intimacy with its audience. Beyond mere reflection, art serves as a portal to forgotten histories and hopeful futures. In the face of enormous obstacles, Kashmiri artists are archiving their stories and preserving identity, deeply rooting themselves in the valleys that they call home, immortalizing their histories for generations to come.

Sarah Awan is a Kashmiri-Australian writer, Social Innovation Practice Fellow at the University of Cambridgeand Board Member at Brooklyn-based non-profit, Girl Be Heard.