Since the liberalization of the Indian economy, the middle class has only heard of the promises of the Neoliberal state made to them and has been aspiring for a better standard of living. It has never imagined the perils of the neoliberal state that would engulf it in its effect and consequences someday. Some of which are but are not limited to unequally available education and healthcare services. The middle class which was already facing mild repercussions of the declining unemployment rates in the country was seriously affected during the pandemic facing the full brunt of the broken health infrastructure and a crippling economy.

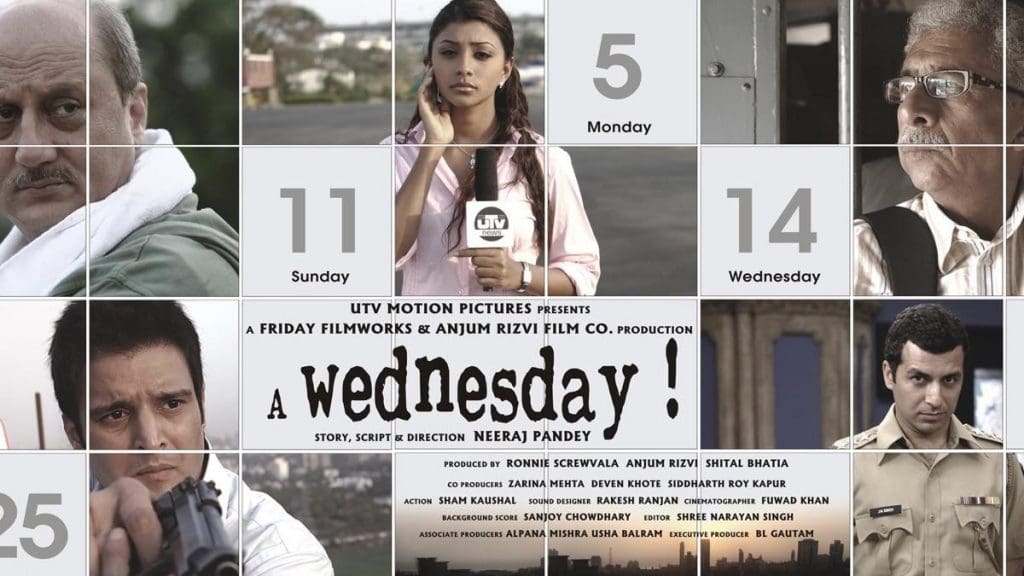

Though there is an extensive economic debate over the definition of the Indian middle class, this article attempts to dissect the popular image of the Indian middle class and tries to answer how this image was created through the popular media and who was left out of the frame. It does so through Naseeruddin Shah’s movie A Wednesday that came out in the year 2008. It was received as one of the best movies of the director Neeraj Pandey and has also inspired a Hollywood remake A Common Man (2013) starring Ben Kingsley. 2008 was the same year when later the Bombay Attacks had taken place.

The decades of the 1990s and early 2000s had an altering effect on India’s politics and economy. On the global front, the 9/11 attacks had happened and the US had subsequently launched an ‘anti-terror attack on Afghanistan. These particular episodes had a ripple effect on global and national politics elsewhere and led to the demonization of Muslim identity as a ‘terrorist’ that had thus begun. In India, the early 1990s had seen a rapid economic liberalization boosting the economy and which in turn led to the growing aspirations of the ever-increasing middle class. The same period saw the resurgence of the Hindu-right wing and a series of communal violence breaking out in Northern India. Indian nation’s unfolding destiny had promises anew for the middle-class man who in the common parlance came to be referred to as an ‘aam aadmi’. The nation was now building upon his aspirations.

Against this backdrop, A Wednesday becomes clear in its message of a common man claiming and re-claiming India. Re-claiming it from the alien who is posed as an enemy. A nation that creates a sense of collective identity and a sense of belongingness. This collective sense comes out of the essence of the homogeneity of the nation to which this common man belongs. Nation-building on this collective ‘homogenous’ identity of a common man then has to combat differences arising from different identities based on region, caste, or ethnicity. In achieving this sense of a utopian homogenous identity, the nation makes an alien or the other who is neither a part of collective identity nor is supposed to feel belonged (Pandian, 2009). This alien or the other, when looking in the context of India since the 1990s, is a Muslim. The image of the other, Muslim in this case is constantly created through what Gramsci would call the dominant narrative or Francois Lyotard might call it a metanarrative. The Bollywood movies as part of the popular culture and media in India has been doing the same with the Muslim identity. Either Muslims are shown as gangsters or mafias or terrorists. Stereotyping even their physical appearances wearing a skull cap, kohl in their eyes and keffiyeh wrapped around their necks.

These images are actively built throughout Bollywood’s history. A Wednesday is no exception in this. While branding Muslims or anything that symbolizes Muslims as a threat to India and its security, the movie fosters the difference between a good and a bad Muslim but presents the idea that even a ‘good’ Muslim can be a potential threat. It makes heroes out of the upper-caste police officers. One is the head who is sound and rational, and the other is a subordinate who is leading a peaceful family life. On the other hand, the Muslim subordinate police officer is shown as deviant, violent, and uncontrollable.

The majority’s “fear of small number” as MSS Pandian quotes Arjun Appadurai (2009) is something that the movie presents through and through. In a scene in the movie, there is shown a lead actor of Bollywood, a role played by Gaurav Kapoor comes to the police officer to file a complaint and calls himself a minority in the film industry. He states the hegemony of the Khans in the film industry that renders the Hindu upper-castes like a Khanna himself as a minority. Further, anything that symbolizes a Muslim identity or is a Muslim identity marker is shown with a demonizing lens and is posed as a threat in the movie. For example, when police personnel introduce the four Muslim ‘terrorists’ to the commissioner, the consequent talk mentions the places like madrassas as the breeding ground of terrorists where young Muslim minds are trained in arms and ammunitions. Whosoever is aware of the institution of madrassas knows that these are the places where the children from lower-class Muslim families and other communities study.

These institutions serve as symbols of “pre-existing inter-religious accommodation” in the words of Pandian (2009) and these are the very symbols that become a source of nationalist anxiety. The national anxiety is built against the minority and on the seeming threat that the minority is thought to pose. As in the introduction of one of the ‘terrorists’ named Mohammad Zaheer who was a software engineer, the police person says that he was systematically brainwashed and was taken to Pakistan and from there he was sent to Afghanistan where he was trained. He further adds that this person has made a website called “www.indiakitabahi.com” wherein the agenda of all of these four ‘terrorists’ to harm the Indian nation is made amply clear.

All of the four Muslim ‘terrorists’ identify themselves with the terror attacks of 1993 and 2006 and 2002 Gujarat riots on-call with the ‘aam aadmi’ who they think has come to rescue them. What is interesting here is that a Muslim individual is shown to be taking responsibility for the anti-Muslim pogrom that had happened in Gujrat in 2002 thus absolving the nexus of politicians and the Hindu-right that was behind the Gujarat episode of violence.

After the whole movie builds on the demonization of Muslim as an individual and a community just to fleetingly name a Muslim somewhere as a victim, the commissioner leaves the ‘aam aadmi’ nameless towards the end saying that people identify religion from one’s name. A Wednesday ends with this paradox of not identifying the Indian common man with his religion but the terrorists as Muslims and an enemy of the Indian nation.

One must ask why is it important to discuss a decade-old movie right now when the country is still trying to overcome the ravages of the pandemic. Then one must also go back to the initial days of the pandemic when the Muslims were being framed as Covid spreaders and the entire Tablighi jamaat episode narrative was being built. Through false and old videos, the jaamtis were shown to be licking plates and spoons and they were also booked under the National Security Act. The uncivilised and inhuman Muslim man is easily taken to be an evil man who wishes bad for the country and hence goes out on the spree of spreading the disease. Such episodes make it even more important for us to revisit the popular Hindi cinema to point out what Althuser calls ideological state apparatuses that use methods other than violence to achieve the desired repression that he calls a repressive state apparatus. These methods include social media and pop culture that are used to disseminate the ideologies of the dominant class.

One must also understand that the country finds itself in the present state due to the economic and political reforms that turned the Indian “welfare” state into a neoliberal one. These reforms gained a religious colour post-2014 but at the crux of it has always been the economic and political aspirations of the Indian middle class that the neoliberal Indian state and government seeks to cater to. One must know that the Indian middle-class man as conceptualized, framed, and popularized in Bollywood is a man who leads or wants to live a happy family life. How can a Muslim man be fitted into this image who is criminalized and shown and further seen as a barbaric, destructive and violent man thus antagonistic to the aspirations of the Indian-middle class and hence the “development” of the country?

This became clearer post-2011 anti-corruption movement. However, now when the Indian middle class is discomforted at the hands of the pandemic and the collapsed health infrastructure to such an extent where the concern from the better standard of living and having a better choice under the neoliberal regime had come down to the choice of life and death. The Indian middle class must identify the real enemy and the problem within its electoral choices. It will have to revisit and redefine its political and economic aspirations for itself and for the country.

Areesha Khan works as a research assistant at Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati.

References

Mamdani, M. (2002). Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: A political perspective on culture and terrorism. American anthropologist, 104(3), 766-775

Pandian, M. S. S. (2009). Nation Impossible. Economic and Political Weekly, 65-69

Tagore, R. (2021). Nationalism. Sristhi Publishers & Distributors.